VOL. 1 EPISODE 6: THE INTERNAL REVOLUTION

The American Revolution didn’t just create a new nation, it created a new way of thinking. We discuss how religion, philosophy, and politics fused to form a distinctly American worldview.

INTRODUCTION [00:00-02:30]

The American Revolution. If you grew up in America, you grew up hearing this story. Hearing of the bravery of the Founding Fathers who broke away from a tyrannical British monarch, hearing of those few colonies who, despite facing one of the largest empires in history, fought for freedom and liberty and united themselves into a new and independent republic.

Today, we’re going to talk about the Revolution but we’re not going to talk about the war. We aren’t going to mention a single battle. Here’s why...

Thirty years after the war ended, John Adams reflected on the Revolution in a letter to a friend. “What do we mean by the American Revolution?” he asked, “Do we mean the American war? The Revolution was affected before the war commenced. The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people… This radical change in the principles, opinions, sentiments, and affections of the people, was the real American Revolution.”1

Today, we’re going to do some intellectual history. This is some of my favorite stuff to study, because we’re not just going to look at what the colonists did but how they thought. We’re going to look at the philosophical beliefs that shaped how they understood the worl

How does a group of people go from supporting a king to rejecting not just that king but rejecting monarchy altogether? What were the religious beliefs of the founders? How did they justify this political and social upheaval? These are the questions we’ll be addressing.

What happened was this:

In the Revolutionary era, the Colonists embraced republicanism, Enlightenment philosophy, and evangelical Christianity. These three philosophies merged with each other to create a distinctly American worldview and ethos. If you want to understand American religion, politics, and culture, looking at this process is vital. Let’s dig in.

--Intro Music--

[Welcome to American History Remix, the podcast about the overlooked and underexplored aspects of American history. We’re glad you’re here!]

OUTLINE AND RESEARCH [02:30-02:52]

Before we get any further, we want to note that in this episode we’re going to move thematically, covering Republicanism, Evangelicalism, and Common Sense Philosophy. In each section, we’ll define the belief, discuss early opposition to it, explain how colonists came to embrace it, and then discuss how it shaped American culture.

REPUBLICANISM [02:52-14:37]

Let’s start by breaking down republicanism. To be clear, we’re not talking about the Republican party. We’re discussing republicanism, the political philosophy after which the party is named. Just remember that, throughout this episode, our usage of republic, republican, republicanism, republicanite, whatever, is not referencing the political party.

So, what is republicanism? Unfortunately, it’s difficult to define. There are a lot of iterations of republicanism. In essence, it’s a form of representative government. It’s also a political philosophy centered around two main themes: a fear of illegitimate power and what one historian called a “nearly messianic belief in the benefits of liberty.”2

Government, in this philosophy, was a necessary evil. Its supreme role was to protect individual freedom. But there is more to it. In a healthy republic, individuals would seek the good of the republic over their own interests. This is what republicans called virtue. Virtue is critical to the whole system. It was a willingness to sacrifice private interests for the sake of the community. Civic virtue was disinterested in individual wants in service to the state.3 The goal was a community of virtuous citizens whose service to the republic would transcend their own passions and desires.

In republican philosophy, the opposite of virtue was vice. And, vice was just as dangerous to the health of a republic as unchecked power. Vice was when citizens acted selfishly and valued luxury over public service. It therefore led to social decay. Unchecked power and self-service promoted tyranny. It would destroy individuals, the society, and ultimately the state.4

Now, we need to qualify some of this, because republicanism did not mean equality for every person, but equality for citizens. In fact, many early champions of republicanism were suspicious of outright democracy.5 Representative politics doesn’t need to be fully democratic. The most obvious example of this is race. In 1790, the first United States Congress passed the Naturalization Act which limited citizenship to “free white persons.”6 Many people living within the republic were therefore not citizens and not equal.

But there wasn’t just a racial divide. There was also a class divide. The revolutionary elite mistrusted poor, laboring men, without land of their own. They believed the poor were idle, lazy, susceptible to vice, and therefore could not be trusted with citizenship.7

Champions of republicanism believed only those who were financially independent could practice virtue. They weren’t dependent on wages from a boss. Their wealth was a sign of their virtue. Who were these people? Landed gentlemen.8

Land ownership was an extremely powerful thing in English society. Check out our previous episode on the colonial environment if you want to learn more.9

One interesting point is that, even though Revolutionary-era republicans excluded large portions of the population from citizenship, namely women, African Americans, Native Americans, and the landless poor, the ideals of the Revolution and the language of liberty and equality excited the aspirations of marginalized groups. As each of these groups later fought for their rights as citizens, they cited the language and promises of the founders, most especially Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence.10

To summarize: a healthy republic would protect citizens from tyranny, and the citizens would resist vice and self-interest and instead seek the good of the republic.

Let’s contrast these ideas with monarchy. For those of us who grew up in America, it can be difficult to see what was so radical about republicanism.

But these were two very different social orders. The purpose of a republican government was to protect the liberty of its citizens. In a monarchy, the responsibility was on the subjects to show honor and deference to the Crown.11

Let’s examine this a little more. The Book of Homilies, which we’ve referred to before, was published by the Anglican Church in 1547 and contains a piece titled “An Exhortation Concerning Good Order and Obedience to Rulers and Magistrates.”

We’ve pulled out several selections from that piece to illustrate the importance people at the time placed on social and political hierarchy.

Let’s cue some Johann Sebastian Bach. Thank you.

The sermon states: “Almighty God hath created and appointed all things, in heaven, earth, and waters, in a most excellent and perfect order … In earth he hath assigned...Kings, princes, and other governors under them, all in good and necessary order … Every degree of people in their vocation, calling, and office [He] hath appointed to them their duty and order: some are in high degree, some in low, some Kings and Princes, some inferiors and subjects, Priests and laymen, masters and servants, fathers and children, husbands and wives, rich and poor, and everyone have need of [the] other … Let us all therefore fear the most detestable vice of rebellion, ever knowing and remembering that he that resisteth...common authority, resisteth...God and his ordinance.”12

This is obviously an idealized view of society. No kingdom did this perfectly. But this expresses how people thought the world should be. It expresses how they understood power.

One way to think about these different beliefs is to think about which direction power flows. In a monarchy, the king has power, the aristocracy below him, peasants on the bottom.

In a republic, powers flow from the bottom up. The power of the ruler is derived from the consent of people.

In the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail, the peasant Dennis tells King Arthur, “supreme executive power derives from a mandate from the masses.”13 That is exactly right.

These are two very different world views.

So, how in the world did people born and raised in this worldview reject monarchy and embrace republicanism?

There was some historical precedent for resisting the power of a monarch. In the one hundred and fifty years prior to the American Revolution, the English Crown was systematically weakened, while the power of Parliament increased. In the 1640s, England broke into a civil war that left their king beheaded and the nation under the rule of Oliver Cromwell. After a decade, Cromwell was beheaded, and England restored the monarchy. Then, in 1688 they had the “Glorious Revolution” where their king ceded much of his power to Parliament.14

King Charles I having a very bad day due to his own beheading. Formerly attributed to Jan Weesop, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

With these events in mind, we can see that the American Revolution was part of a larger trend away from monarchy. But at the same time, the American Revolution is a little peculiar. Unlike many other colonies who rebelled against their imperial masters around the same time, the American colonists were not an oppressed people. They were economically sound and experienced more freedom than most eighteenth-century imperial subjects.15

However, there were many differences between the subjects in England and in America. Both had merchants, landowners, and the poor, but the American colonists didn’t have the lords and nobles in between the king and the lower classes. In this way, colonial society was much more truncated than English society. There were also economic differences. The colonies were more dependent on agriculture and produced different types of crops than they did in England. Finally, colonial society had complex relations with Native Americans of which there was no parallel in England.16

These differences helped widen the gap between the colonists and the motherland.

The final break came after the Seven Years War, when the Crown reorganized the empire and implemented a series of new colonial policies, including new taxes, trade restrictions, barring western settlements, and housing a standing army on the continent. These were the social and political pressures that pushed the colonists away from monarchy. Check out our previous episode if you’d like to learn more.

Colonists disliked these policies and their frustration was amplified by the fact that they had no representation in Parliament, but they did not jump to rebellion immediately.17 A large portion of the population couldn’t imagine separating from the Crown. Many were not ready to be cut-off from the military and economic perks of being tied to England.

But, over time, as tensions between the Crown and colonies grew, once-loyal subjects began to embrace a new social and political order.

Republicanism gave the colonists another philosophy to embrace as they rejected monarchy. If you’ve ever changed your views on an important subject, you’ve probably experienced that it’s easier to leave one school of thought if you have another belief system to embrace. It’s easier to abandon socialism and embrace capitalism, or to reject capitalism and embrace socialism. It’s harder to detach yourself from capitalism, socialism, feudalism, whatever, and not replace that belief with a new one, to remain, in this example, an economic agnostic. That’s a hard spot to stay long term.

This is what republicanism offered the colonists as they broke away from monarchy. With an established precedent of representation in Parliament which checked the power of the Crown, the Revolutionary generation embraced republicanism as a new way to order their society.

EVANGELICAL CHRISTIANITY [14:37-25:58]

But republicanism wasn’t the only idea at play. In fact, American republicanism looked similar to other iterations of republicanism in the past. But there is one very significant difference—the role of evangelical Christianity.

Evangelicalism is another tricky word to define as it has undergone enormous change over the centuries and was loosely defined to begin with. For our purposes, evangelicalism means a form of Christianity that was centered around the authority of the Bible, the centrality of Christ, emphasized a conversion experience, and promoted religious activism.18 Evangelizing, if you will.

America’s history with republicanism and evangelicalism is peculiar. As other nations and colonies moved away from monarchical authority, they became more secular, but Americans became more religious.19

It’s even more surprising when you consider that religious leaders were initially skeptical of radical politics like republicanism. Republican philosophy encouraged people to focus on this world rather than have an otherworldly focus. It downplayed God’s sovereignty by insisting that people could govern themselves. And it disrupted the social order.

Let’s look back to the Book of Homilies, remember “He that resisteth common authority, resisteth God and his ordinance.” When there was no separation of Church and State, to reject the State was to reject God. To reject hierarchy was to reject God’s order of the world. This didn’t sit well with Christians at the time.

Furthermore, it was difficult for Christians to embrace republicanism at first, because many early champions of republican political philosophy rejected Christianity. By association, they would be embracing the philosophy of heretics and radicals. For example, in the French Revolution, which began in 1789, republicans rebelled not just against the monarchy but against the Church.20

What happened in America was different because these ideas, evangelicalism, and republicanism, joined together in the minds of the people. So, how did this happen?

The merging of these beliefs did not occur at once, but gradually.

One of the key developments was the two philosophies began to share a common language. Christians found a use for republican language, especially in the wake of the conflicts between England and France. Religious leaders in the colonies, motivated out of a fear of Catholicism, began using republican terms such as tyranny, slavery, liberty, freedom, and abusive power when criticizing Catholic France and the Pope.21

As we discussed earlier, virtue and vice were key concepts in republicanism. Republicans meant a humanistic virtue, a Machiavellian virtue that sought the good of the state above all else.22 Christianity also celebrates virtue and denounces vice. Christian virtue is a devotion to God above all else.23

So, in this case, they were using similar words to describe different things. But, once the two groups were speaking a shared language, regardless of the ambiguity in the terms, the ideas began to intertwine.

Thomas Paine, Founding Father and author of Common Sense (1776) which argued for American independence from Britain. Laurent Dabos, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Champions of republican philosophy also began using religious language to promote their ideas among religious people. Thomas Paine, who was not a Christian, cited passages in the Old Testament where Israel had no king. He did this to support the idea of republicanism.24

He wasn’t alone either. Many republicans in the colonies believed that Christian morals would ensure a virtuous population and therefore ensure a healthy republic.25 In his diary, John Adams reflected on Christianity with admiration, he wrote “one great advantage of the Christian religion is that it brings the great Principle of the Law of Nature and nations, Love your Neighbor as yourself...[to] the whole people.” For Adams this was useful because “No other Institution for Education, no kind of political Discipline, could diffuse this kind of necessary Information, so universally among the Ranks and Descriptions of Citizens.”26

Notice what he’s saying. He is not saying it is right to worship the Christian God because God is good and because it is the supreme duty of mankind to submit to and find joy in the goodness of God. No, in this view, Christianity was a means to an end rather than the primary importance in life. It was a way to support the state.27

So, a shared language and a recognition of the usefulness of each philosophy allowed the ideas to merge in the minds of the people.

Let’s pause here and talk about religion during the Revolutionary generation, because a lot of people have strong feelings about this subject.

The American Revolution was sandwiched between two Christian revivals, what we call the First and Second Great Awakenings. The first occurred in the 1740s and was centered around figures such as Jonathan Edwards and George Whitfield. These preachers traveled throughout the colonies preaching the Christian faith and the need for salvation.28 We discussed this in more detail in our episode on Puritanism. The Second Great Awakening began in the 1790s and reached its peak between the 1820s and 1840s. In this era, church attendance in America grew dramatically.29

The Revolutionary generation experienced no such revival. The First Great Awakening had sparked an increase in church membership, but afterwards the rates again declined. From 1740 to 1780, the number of churches in the colonies increased but at a much slower rate than the population increased. The evidence suggests that as few as one out of every twenty people were members of a church.

We can see a similar trend in the works that were published in the colonies at this time. In 1700, 85 percent of that years’ publications were religious in nature. In 1750, it was only 35 percent. In 1775, on the eve of independence, political writings dominated the culture. Only 16 percent of published works were religious.30

The war itself contributed to this decline. It’s not too surprising that individuals were more interested in political events during a political revolution. But churches at the time still lamented the “low and declining state of religion among us.”31

So, that was the general public. What about the Founding Fathers?

Samuel Adams and Patrick Henry were the most prominent orthodox Christians among the Founding Fathers. But these two were the exception.32 The majority of the founders were, in varying ways, unorthodox. George Washington remained ambiguous during his life about his beliefs; others only started claiming he was a devout Christian after his death.33 John Adams did not believe in the divinity of Christ.34 Thomas Jefferson also did not believe in the divinity of Christ, and he even created his own version of the New Testament that omitted miracles and Christ’s resurrection.35 In 1776, Thomas Paine published a pamphlet called Common Sense, which we referred to before, this is where he cited the Old Testament to garner Christian support for republicanism. Privately, however, he did not believe in scripture. He later wrote that most of the Old Testament of the Bible “deserves either our abhorrence or our contempt.”36 These, collectively, are not the views of orthodox Christians.

The Jefferson Bible, an example of deistic philosophy, a version of the gospels which left out the miracles performed by Jesus and his resurrection. Thomas Jefferson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Constitution was a remarkably secular document for that time. It ensures the freedom of religion but makes no other mention of God. In 1789, someone asked Alexander Hamilton why the founders made no mention of God. Hamilton replied by saying, “we forgot.”37

Does this mean America wasn’t a Christians nation at all? No. While the founders were, with few exceptions, not Christians, their most radical personal religious views did not catch on with the general public.38

Even though church membership was low at the time, there were still many people who were sincere, practicing Christians. There were also those who were not as strict in their beliefs, or perhaps not even Christian at all, but nonetheless lived in a culturally Christian atmosphere and invoked religious ideas and language.39

Complicating the story is the fact that, even though the founders were unorthodox and church membership was low during this generation, the first decades of the nineteenth century saw a surge in evangelicalism—the beginnings of the Second Great Awakening. So, Christianity spread after the founding of the nation. And this growth was dramatic. We’re going to talk about it more in a future episode.

We realize this is a controversial topic. On one side, some will claim that America was uniquely founded as a Christian nation. On the other side, some will claim that it was founded as a specifically secular nation. Both extremes miss the mark. The truth is...it’s complicated. This is a story that doesn’t sell well, because it’s not simple and easily packaged. It doesn’t make a good headline or a Twitter post. It takes to time unpack the complexity of religious belief in this era.

COMMON SENSE [25:58-36:09]

Alright, let’s recap what we covered so far.

During the Revolutionary generation, colonists began to embrace republicanism. Many Christians were originally skeptical of republicanism, but they eventually came to accept it. Republicans, meanwhile, regardless of their personal beliefs, promoted Christian morality because it would support the republic.

Now we add another wrinkle to the story—Common Sense Philosophy.

This was a branch of the Enlightenment. For those unfamiliar with it, the Enlightenment was an intellectual movement that emerged in Europe in the sixteen and seventeen hundreds. The movement was multifaceted.

Philosophers like Voltaire, Rene Descartes, and John Locke (just to name a few) emphasized the ability of human reason. The world, these philosophers argued, was not mysterious. It was ordered and predictable, and mankind possessed the ability to understand it. They also spoke of innate and inalienable rights which belonged to all humans. This was also the birth of modern science with the scientific method we still use today. Figures such as Galileo and Isaac Newton made precise observations about nature. There was an effort to understand the world in a “reasoned, orderly, and verifiable way.”40

A bunch of philosophers gather round to read Voltaire, 1755. Anicet Charles Gabriel Lemonnier, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Expanding on these views was a group of Scottish philosophers, such as Thomas Reid, Dugald Stewart, and John Witherspoon, who developed the school of Common Sense Philosophy. The philosophy essentially proposes that, not only does man possesses the innate ability to reason, but there are also universal human instincts common to all men. Thus, from what they called “self-evident truths,” and “laws of nature,” man can use his reason to deduce the nature of reality and morality.41

We don’t want to get lost in the weeds of Enlightenment philosophy, but it is perhaps easier to understand this view if we contrast it with another view.

Not all Enlightenment philosophers celebrated commonsense. John Locke, for instance, was an English philosopher who argued that mankind possesses the ability to reason but did not believe there were universal truths obvious to everyone. Instead, knowledge of reality and morality had to be gained through experience, it was not innate.42

Both of these schools of the Enlightenment are present in American culture, but it is the commonsense variation that has been most influential and was the most important to the Revolutionary generation and the Founding Fathers.

Common Sense Philosophy is so engrained in the American psyche that it can be difficult to see, but once you notice this thought pattern, you’ll see it everywhere.

For example, have you ever been in a discussion with someone and, instead of citing specific evidence to prove their point, they say something like, “I just don’t see how this can be true” or “This is just the way I see it”? In doing this, they are appealing to common sense. They are exercising their belief that their personal intuition is authoritative.

Here’s a more specific example: I once was talking with someone who said that they believed all elections in America were fixed, the results predetermined, an argument they used to justify not voting. When asked to provide any evidence to back-up their argument, they said, “That’s just what I think.” To them, it was self-evident, it needed no justification.

These ideas are also present in the way we think and talk about morality. When we say people should follow their conscience or refer to an internal moral compass, when we expect others and ourselves to intuitively know right from wrong, we are, knowingly or unknowingly, referring to common sense.

This philosophy permeates American thought.

Human intuition was not a new concept to eighteenth-century American colonists, but its trustworthiness evolved as it was championed by Enlightenment philosophers. But, like republicanism, this philosophy was threatening and uncomfortable to many Americans at first.

Self-evident truth is a long way from the Puritan belief in the unreliability of the human heart. Puritanism as a form of society had already collapsed in the colonies, but Puritan ethics and worldview were still alive and influential on many Americans.43 Puritans argued that man was inherently sinful and that his heart and mind must be brought in alignment with God and scripture.44 Puritans emphasized the sinfulness of the human heart apart from God. God was therefore necessary to reveal the nature of right and wrong. A philosophy which left God out of ethics, as one contemporary described it, only “pretends to give religion.”45

The American Revolution itself helped change this opposition. Common Sense Philosophy was incredibly useful in defending the Revolution and was fully embraced by the Founding Fathers.

In order to justify a revolution against a king, you have to appeal to something higher than the king. What’s higher than the authority of a monarch or parliament? How about universal “self-evident truth”, “unalienable rights,” and the “laws of nature.”46 That’s a pretty good authority.

Common sense also bolstered republicanism because it supported the idea that men had the capacity to govern themselves. Again, the work of Thomas Paine is representative. That pamphlet we keep mentioning that drew together Christianity and republicanism was called Common Sense.

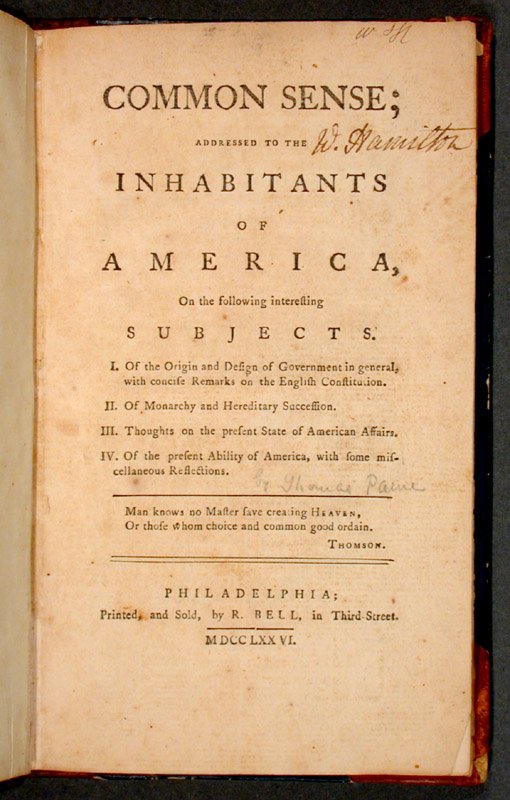

Cover of Thomas Paine’s pamphlet, Common Sense. 1776. Scanned by uploader, originally by Thomas Paine, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

So, just as American evangelicals embraced republicanism, they began to embrace Common Sense Philosophy.

And this in turn altered American evangelicalism.

Puritans had believed it necessary to carefully study scripture and, even then, they were dependent on God’s revelation to understand it. In the Catholic tradition, scripture was interpreted by the authority of the Church. Even in the Gospels, the disciples knew scripture but did not understand it until its meaning was revealed to them by the Holy Spirit.47 But American evangelical interpretation of scripture assumed that its meaning was obvious to anyone. Just as truth in nature was simple and self-evident to anyone with reason, they began to believe that the meaning of scripture was also simple, plain, literal.

The giant figures of the Protestant Reformation, such as Martin Luther and John Calvin, championed the idea that scriptures should be available to all. However, they warned that a disordered and jumbled combination of biblical passages could make scripture appear to say anything one wants. In one of my favorite quotes in human history, Luther, the founder of the Reformation, said that if people would accept ill arranged and un-careful interpretations of scripture, then he could certainly “prove with Scripture that Rastrum beer is better than Malmsey wine.”48 What is he saying here? He’s warning his followers to be careful not to interpret scripture carelessly to make it serve their own ends. You want me to use scripture to prove that the Green Bay Packers are God’s team? Gladly, I’ll do it! I’m kidding. Sort of.

Instead, figures like Luther and Calvin argued for an interpretation of scripture that required careful study and guidance from trained ministers.49 In essence, they claimed that the meaning of a passage in scripture was not necessarily plain or obvious.

American evangelical Christianity largely disregarded this advice.

In essence, this democratized American Christianity. The Revolution and the ideological shifts which accompanied it, inverted Church authority.50 There was an appeal to the “common man.” During the revivals which occurred after the Revolution, preaching styles became much less formal and more vernacular. Congregations wanted “self-evident and down to earth doctrines.”51

Common Sense Philosophy and this populist evangelicalism gave rise to biblical literalism.52 No need to understand the original language or culture or historical context. Anyone could interpret scripture. Just open it up and read. Its meaning was simple and plain.

All this explains why literalist interpretations of scripture - young earth creationism, for example - are common in American evangelical Christianity but not nearly as common in global Christianity.

Like I said, Common Sense Philosophy is everywhere in American thought. Its influence is far reaching.

It reshaped the American church, it reinforced republicanism, and it justified the American Revolution. It also venerated the common man. “Self-evident truth,” “unalienable rights,” and the “laws of nature” put authority in the hands of reasoning individuals, not kings or even God. An Englishman may have appealed to tradition, a Catholic to the authority of the Church, or a Puritan to scripture, but Thomas Jefferson, when he wrote the Declaration of Independence, began by saying, “We hold these truths to be self-evident.”

Common sense.

Depiction of the Second Continental Congress which issued the Declaration of Independence in 1776. John Trumbull, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

CONCLUSION [36:09-38:37]

Republicanism, evangelicalism, and Common Sense Philosophy, despite their initial conflicts and even hostility, merged.

Older ideas about the nature of mankind, of knowledge, human reason, social hierarchy, the nature of power, all of these were reshaped or overturned. The result is something modern Americans can recognize as American culture and thought.

Organizing this episode was a huge pain in the butt. Because the three views we’re talking about weren’t accepted in a specific order. It wasn’t A therefore B therefore C. It was A, B, and C all at once and mutually influencing each other. It wasn’t a certain order of events, but the evolution of an ethos.

These ideas are powerful, not because we think them, but because we Americans assume them without noticing. They are buried down deep in the American psyche.

Without this internal intellectual revolution, Americans still could have rebelled against King George, but perhaps would have crowned another king. In the history of the world, there have been plenty of rebellions that overthrew one king and created another. But that’s not what the colonists did. They did something more. They remade their entire worldview. The political revolution was in a sense the outworking of a deeper change which occurred within the American people.

Thanks for listening.

[American History Remix is written and produced by Will Schneider and Lyndsay Smith. Thank you to our friends who helped bring this project to life—Allie Gavette, Sari Field, and Josh Jones. And thanks to our families—to Naomi, Nora, our dog Sam, and CJ. To everyone else, be sure to follow us on Instagram and Twitter. We’ll see you in Volume Two – The Early Republic.]

REFERENCES

Ahlstrom, Sydney E. A Religious History of the American People. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Anglican Library. “Book of Homilies: Homily on Obedience.” Accessed July 20, 2020. http://www.anglicanlibrary.org/homilies/bk1hom10.htm.

Butler, Jon. Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People. Studies in Cultural History. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1990.

Foner, Eric. Give Me Liberty!: An American History. New York: W.W. Norton, 2011.

Hatch, Nathan O. The Democratization of American Christianity. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

Locke, John. “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.” In Classics of Western Philosophy, edited by Steven M. Cahn, 629-697. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2006.

Morgan, Edmund S. The Birth of the Republic, 1763-89. Fourth ed. Chicago History of American Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967.

Morgan, Edmund S. "Slavery and Freedom: The American Paradox." The Journal of American History 59, no. 1 (1972): 5-29.

Noll, Mark A. America's God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

The Smithsonian. “The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth.” Accessed July 20, 2020. https://americanhistory.si.edu/JeffersonBible/.

Wood, Gordon S. The American Revolution: A History. New York: Modern Library, 2003.

Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. New York: Vintage Books, 1993.

NOTES

[1] “From John Adams to Hezekiah Niles, 13 February 1818,” Founders Online, National Archives, accessed July 20, 2020, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-6854.

[2] Mark A. Noll, America's God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 56.

[3] Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Vintage Books, 1993), 104.

[4] Noll, America's God, 57.

[5] Noll, America's God, 57.

[6] Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty!: An American History (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011), 277.

[7] Edmund S. Morgan, "Slavery and Freedom: The American Paradox," The Journal of American History 59, no. 1 (1972): 9-10.

[8] Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, 104-105.

[9] The episode is titled: “Native Americans, Colonists & Nature.”

[10] Mark Fiege, The Republic of Nature: An Environmental History of the United States (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012), 75-93.

[11] Noll, America's God, 55-56; Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, 95-97.

[12] “Book of Homilies: Homily on Obedience,” Anglican Library, Accessed July 20, 2020, http://www.anglicanlibrary.org/homilies/bk1hom10.htm.

[13] Monty Python and the Holy Grail, directed by Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones (1974; Culver City, CA: Columbia TriStar Home Entertainment, 2001), DVD.

[14] Gordon Wood, The American Revolution: A History (New York: Modern Library, 2003), 13.

[15] Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, 4.

[16] Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, 112.

[17] Edmund S. Morgan, The Birth of the Republic: 1763-89 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967), 16-17.

[18] Noll, America's God, 5.

[19] Noll, America's God, 87-88.

[20] Noll, America's God, 87-88.

[21] Noll, America's God, 78-82.

[22] Noll, America's God, 58, 90.

[23] Noll, America's God, 90-91.

[24] Noll, America's God, 83-85.

[25] Noll, America's God, 63-64, 203.

[26] Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 366.

[27] Noll, America's God, 57-59.

[28] Noll, America's God, 42-44.

[29] Noll, America's God, 179-86.

[30] Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People, 365; Noll, America's God, 162-63.

[31] Jon Butler, Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990), 208.

[32] Noll, America's God, 82; Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People, 364.

[33] Noll, America's God, 205.

[34] Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, 330.

[35] “The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth,” The Smithsonian, accessed July 20, 2020, https://americanhistory.si.edu/JeffersonBible/

[36] Noll, America's God, 83-84.

[37] Noll, America’s God, 207-208.

[38] Noll, America's God, 143.

[39] Noll, America's God, 164.

[40] Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People, 352-53.

[41] Noll, America's God, 93-95; Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People, 353-56.

[42] John Locke, “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding,” in Classics of Western Philosophy, ed. Steven M. Cahn (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2006), 629-33.

[43] Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People, 349.

[44] Noll, America's God, 96.

[45] Noll, America's God, 97.

[46] Noll, America's God, 110-111.

[47] Luke 24:44-46.

[48] Nathan O. Hatch, The Democratization of American Christianity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 180.

[49] Hatch, The Democratization of American Christianity, 179-83.

[50] Hatch, The Democratization of American Christianity, 45.

[51] Hatch, The Democratization of American Christianity, 9.

[52] Noll, America's God, 379-85.