VOL. 2 EPISODE 4: EARLY URBANIZATION

Cholera, fire, violence, and manure. Life in antebellum New York was exciting, dirty and filled with class conflict. We discuss the environmental and social struggles in the early decades of the city’s urbanization.

**This episode contains material which some listeners may find gross. We suggest you refrain from snacking while you enjoy this podcast.**

INTRODUCTION [00:00-03:27]

The English writer Charles Dickens visited New York City in 1842.

One day when the weather was warm, he took a stroll through the city, visiting first the busy thoroughfare of Broadway. Dickens was impressed with the spacious homes, the fancy shops, and the fashion of the women on the street—they wore colorful silks, satins, and hoods. He even tipped his hat to a woman with a light blue parasol. – Dickens, you old rascal!

But amongst the wealthy and fashionably dressed Dickens noted that other New Yorkers were out on the town – pigs. Urban pigs scoured the heaps of debris on the street in search of food.

As he made his way through the city, he reached the Bowery, a working-class neighborhood. The sights, sounds, and smells were different here than on Broadway. The people didn’t seem to be in such good spirits. The shops were less attractive than the ones he saw before, carrying practical rather than luxury goods. And he noted the number of “foreigners.”

Dickens then moved on to the city’s most notorious slum – the Five Points neighborhood.

This neighborhood was dirty. The lanes and alleys were narrow and filled with taverns. Dickens called it a haven for rats and remarked that its residents lived in miserable conditions. The sounds of dogs, pigs, horse-drawn carriages, carts, wagons, and a cacophony of languages and accents filled the air, as did the smells – mud, manure, and grime. It was to Five Points neighborhood that many of those urban pigs returned each night.

The Five Points - painting by unknown artist, circa 1827. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The neighborhood also offered entertainment such as gaming, dancing, and drinking. Five Points was a slum – but a lively one.1

New York City was at the forefront of urbanization in America, and it encountered many of the challenges that other cities would face later on. Today we are looking at the growth of New York City, and we are going to examine two themes: class differences and the physical environment.

As the city grew, its laborers developed a distinct working-class culture which conflicted with New York’s upper class. We’ll look at how the different classes experienced the growing pains of early urbanization when they dealt with the city's filth, disease, water, food, animals, and public spaces.

Examining the themes of class and the environment together reveals a city that was rowdy, energetic, sick, dirty, and rife with conflict.

Let’s dig in.

--Intro Music--

[Welcome to American History Remix, the podcast about the overlooked and underexplored parts of American history. We’re glad you’re here!]

BACKGROUND [03:27-06:17]

When the United States was founded, the Nation was overwhelmingly rural. Most Americans lived on farms or in small communities. In 1820, there were only five cities with a population over 25,000. But, over the following decades, the Nation experienced the largest rate of urban expansion in its history. During this period, the urban population tripled. By 1850, there were twenty-six cities with a population over 25,000.2 New York City was the fastest growing of them all. Between 1810 and 1860, its population went from 86,000 to 813,000.3

New York City consisted only of the island of Manhattan, sitting between the Hudson and East Rivers. Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Staten Island, the other boroughs that are part of the city today, were at that time independent.

The oldest European settlement began on the southern tip of Manhattan and crept north as the population grew. Manhattan was both urban and rural. Bankers and investors worked on Wall Street in the south, while hills, swamps, small villages, and farms dotted the island farther north.

The burgeoning market economy propelled the rapid urban growth, especially after the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, which connected the Great Lakes to New York Harbor via the Hudson River.4 New York became a center for trade and manufacturing. Industries like printing, metalworking, and sugar refining grew significantly.5 Small artisan shops declined as employers established large factories with a large unskilled labor force operating machinery.6

An 1837 map of New York City. Williams, Edwin, 1797-1854, [from old catalog] ed;Disturnell, John, 1801-1877, [from old catalog] pub, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons.

As the city grew it became more diverse. Between 1820 and 1840, 667,000 immigrants came to America. Seventy-five percent of them came through New York City.7

Irish immigration grew steadily in the early 1800s, but in the 1840s the Great Potato Famine struck Ireland. Facing the threat of starvation, many fled the country and journeyed to America, becoming the most prominent immigrant group in NYC.8

Germans made up the next largest group of immigrants at the time. Though Germans tended to move on to other cities such as Buffalo, Chicago, St. Louis, and Cincinnati, many stayed in New York City as well.9 By 1850, 40 percent of New Yorkers were foreign-born.10

CLASS [06:17-13:32]

The market economy also fueled a class divide between the wealthy factory owners and their laborers, between old New Yorkers and recent immigrants to the city.

The city struggled to keep up with the population boom. To meet the growing demand for housing, landowners began constructing tenements and boarding houses.11

Tenements were usually multistory brick buildings, each floor rented to a family. They were cramped spaces, often 2-4 rooms and only 300-400 total square feet. For a bathroom, residents used a bed pan or perhaps an outhouse in the yard.12

Single men often lived in boarding houses. They comprised of multiple bedrooms and a common room for meals. Like tenements, they were also crowded. Men slept two, sometimes three, per bed.13 Boarding houses were usually based on language; German speaking immigrants had their own houses, as did English speakers.14

The poorest of all lived in shanty towns on the outskirts of the city. Some were originally built as temporary shelters but became permanent houses for immigrants who didn’t want to live in the crowded tenement houses.15

Free African Americans, likewise, tended to live in their own communities. One community, dubbed “Little Africa” had many residents who had lived in the Five Points neighborhood but left as that neighborhood grew more violent.16

In 1825 another group of African Americans formed a community called Seneca Village. Located farther north on the island, between what is today 81st and 89th streets, which was then still rural. African Americans chose the site because it was far from the city center where they regularly encountered discrimination and hostility. Besides homes, the village had its own school, cemetery, and three churches.17

The city’s upper class lived in a different environment. Their homes were less crowded. By the 1860s, they even had running water, perhaps gas, and even a bathroom.18

Originally, the city’s wealthy residents lived at the southern tip of Manhattan. But as the city grew, they slowly sold their homes and moved to areas like Washington Square or along the Hudson River. The upper and working classes separated themselves into their own neighborhoods, with Broadway as the dividing line between them.19

The lower class tended to live within walking distance of their work whereas wealthy citizens traveled to work in horse-drawn carriages.20

When they did walk the city streets, the upper class went promenading. In the evenings and after church on Sundays, they would stroll up and down the prominent streets wearing their finest clothes and tipping their hats to other members of high society. It was a means of socializing and displaying their status.21 This is what Dickens saw when he walked through the city.

The lower class had their own form of entertainment, and it wasn’t tipping their hats to well-dressed individuals. Every night the young working-class men frequented the bars, brothels, and theaters of the city.

You see, the boarding houses were instrumental in the development of a shared working-class culture. One resident remarked, “Boarding houses were merely shelters not homes.” So, after work, rather than staying in their cramped, dark rooms without electricity or a bathroom, the men ventured into the city.22

Bull's head tavern in New York City, circa 1800. See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Taverns were a place to drink, socialize, and fight. Men visited several bars each night, buying drinks for their friends and fighting their fellow patrons. Violence became a defining feature of their manhood.23

Men also joined volunteer fire departments. Fire was a serious threat in the urban environment, but the departments were also social clubs. When there weren’t fires (and sometimes even when there were) rival fire departments would race each other, seeing who could pull their carts the fastest. The competitions often turned into violent fistfights, though there seems to have been some rules of sportsmanship. Guns and knives weren’t allowed, just fists and rocks. When the fight was over, the men would even shake hands before they went on their way.24

Theaters also provided entertainment to the masses. In the prior generation, theater was not divided by class; the wealthy and the poor attended together. That remained true as late as the 1820s. But by the 1830s, two separate theater worlds emerged – one for the working class, another for the upper class.25

Upper class theaters were for the elegant and refined. They had formal dress codes and rules prohibiting prostitutes from hanging around the venue.

The working class didn’t care for such theaters with their elitist appeal. They preferred to be rowdy and wild. One critic complained that the typical lower-class theater attendee was ““always half-drunk, except for when he was wholly drunk.”26

Prostitution wasn’t strictly illegal in the city, but women who solicited on the streets could be arrested for vagrancy. This made brothels common in the city. Theater galleries were another place where prostitutes could meet with clients.27

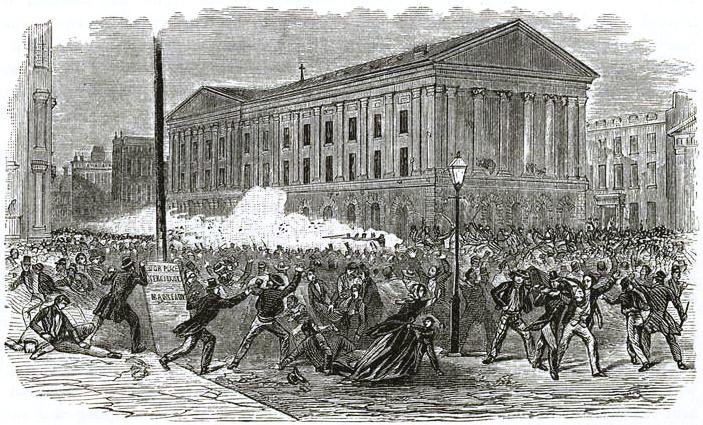

Competition between the two theater worlds could even turn violent. In 1849, Astor Place – an upper-class theater—was hosting a performance of MacBeth. To compete with the Astor Place, the working-class Park Theater put on its own performance of MacBeth.

But that wasn’t enough. Thousands of working-class men gathered outside the Astor Place and began pelting the actor playing MacBeth with eggs. Then they turned to the building itself, hurling rocks at it and trying to breech its doors. The scene turned into a riot and, after the New York militia put it down, 150 people were wounded, and at least 21 dead. Class tensions in the city had erupted into violence…over performances of Shakespeare.28

Astor Place Opera-House riot, 1849. Unknown; cropped by Beyond My Ken (talk) 11:03, 23 October 2010 (UTC), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In all, the upper class viewed the working class as dangerous.29 One New Yorker complained, “the City is infested by gangs of hardened wretches.”30 Class tensions were high.

FILTH [13:32-19:10]

So far, we’ve been talking about class; the social division as well as the energy and feel of the city. Now we want to add another dimension to the story – the physical environment.

New York was an especially dirty place. The streets were muddy and littered with rotten food and trash. It was not uncommon to see dogs, pigs, and chickens rummaging through the garbage piles.

Garbage collectors, or “scavengers” as they were called, were supposed to collect the piles of waste twice a week. However, collection was inconsistent, especially in the poorer neighborhoods. Scavengers would prioritize collecting material they could resell. They would grab scraps of wood or cloth but leave the dead rats to rot there on the street.31

In the winter of 1852, the Tribune ran an article which read, “Some of the workmen engaged in turning up the ice in Broadway yesterday came across a sort of fossil which seems to prove a fact which has been much disputed of late. The fossil was that of a brush broom, and apparently settles the point that at some past age the streets of New-York had been swept.”32 New Yorkers were dirty, energetic, violent, and apparently, sarcastic.

As the city grew, so did the number of horses, which were integral to the city’s daily operations. They pulled carriages and street cars, hauled goods, and powered industrial machinery. Horses also produced a ton, in fact, tons of manure. In 1835, there were 10,000 horses in New York City. Each horse produced about 35-40 pounds of manure each day.33

Fun as it is, we’re not just talking about horse manure to gross you out. It was actually really important. An entire economy developed around manure. It affected people’s livelihoods. Farmers from the surrounding country produced hay, vegetables, and grain for urban markets. To grow the food to feed the city, they needed to fertilize the ground and used urban horse manure to do it. Selling the street manure to regional farmers was a decent living.34

The horse manure industry was so important that even the city government got in on the action. They claimed the streets were public property and thus under their control, and they began collecting and selling the street manure. The urban horses tended to eat random things from around the city like old shoes, building materials, and sand, which decreased the quality of their manure. The city had to appoint manure inspectors before sending the product to farmers. And it was in their best interest to do so, because the food the farmers were growing would find its way back to the city. In general, though, the New York Agricultural Society deemed street manure a “great fertilizer … a compost of earthy substances ground fine” by the many carts and carriages. “A fermentative mass,” they continued, “containing all the elements which nourish vegetation.”35

Whether or not this was true, selling manure was one of the city’s most lucrative businesses. In 1830, the municipal government sold over $19,000 worth of manure. That’s over half a million dollars today.36 They still had to compete with those who sold manure from stables, but the city would fine individuals who collected horse manure from the streets without permission. That was their territory.37

Just as New Yorkers had to deal with horse manure, they also had to deal with human waste.

In 1844, the city council estimated that residents produced between 700,000 and 800,000 cubic feet of excrement a year. So gross. Polite society called the material “night soil.” But to be clear, we’re talking about poop. And remember that those tenements and boarding houses didn’t have plumping.

At least once a year, property owners had to hire workers to empty their privies. The workers dumped the waste into the rivers. But it would pile so much that ships had difficulty docking. The city would then have to pay to have the rivers dredged. This was one of the serious challenges of early urbanization: what do you do with all the poop?

Some people tried to repurpose human waste like they did with horse manure. They turned it into a fertilizer and called it poudrette (from French poudre, meaning “powder”). It…uh…never caught on, and human waste remained a serious problem for New Yorkers until the city finally adopted an extensive sewer system at the end of the century.38

DISEASE [19:10-22:45]

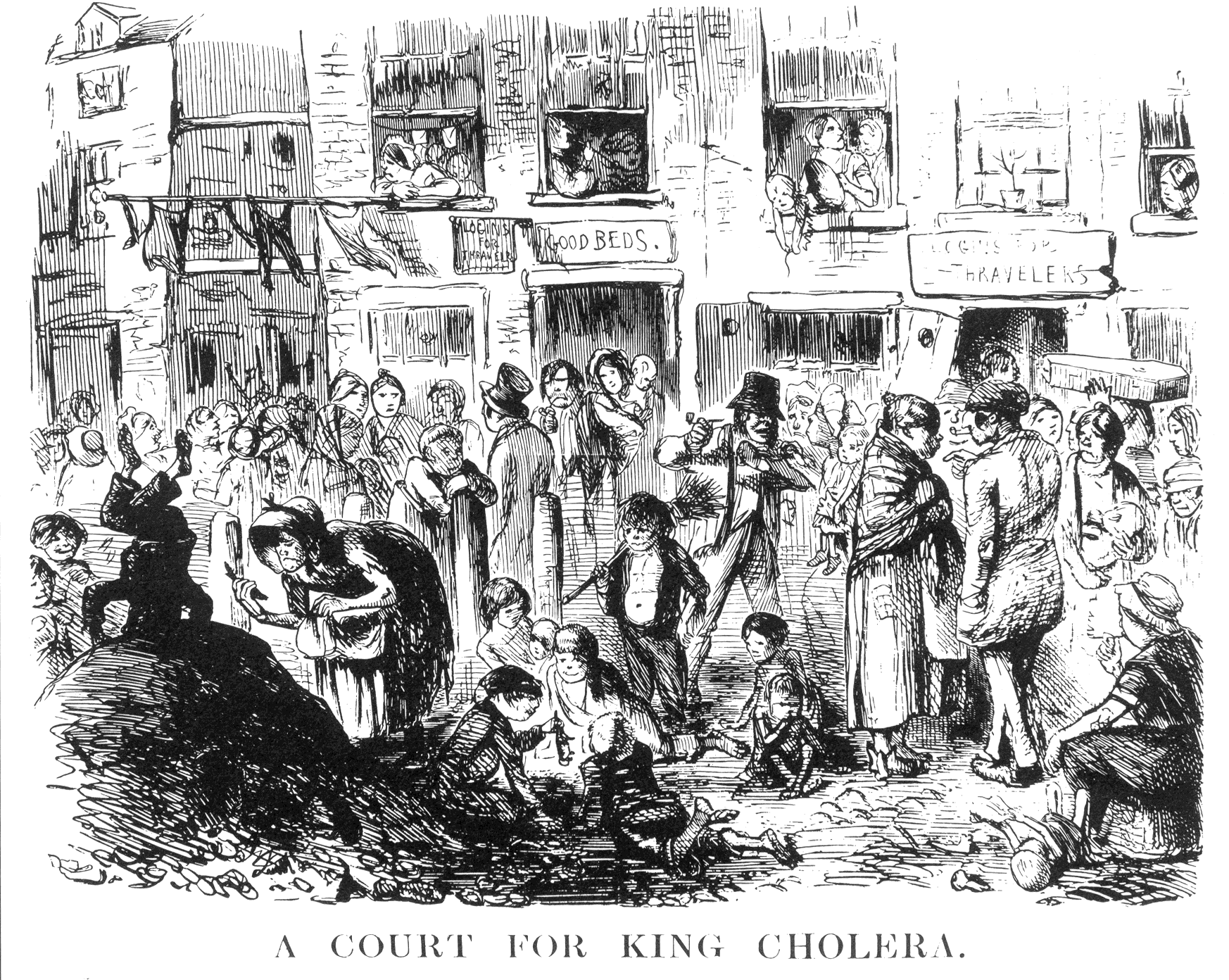

With all this filth, it’s not surprising that the city also dealt with disease. And disease shines light on the class divide – especially when it came to cholera.

Cholera is a bacterial disease which spreads through water and uncooked food. Victims suffer from severe diarrhea and dehydration. It killed about half of those infected, sometimes only hours after they contracted it.39

It began in Europe and spread through its major cities before reaching the Americas in 1832.40 After receiving word that the disease crossed the Atlantic and reached Canada, city leaders began taking measures to protect New Yorkers.

Government officials inspected private residences and white-washed homes, covering them in lime.41 They implemented new street-cleaning policies and taxed residents to cover the cost of professional street sweepers and street inspectors. New York’s streets received a cleaning like never before. One elderly woman who had lived in the city her whole life remarked, “I never knew that the streets were covered with stones before.”42

Cholera hit the city in July 1832. Even with the cleaning, 3000 residents died within the first week. Most of the deaths occurred in the working-class neighborhoods in lower Manhattan.43

“A Court for King Cholera” Illustration, 1852. Source: Stephen J. Lee: Aspects of British Political History, 1815–1914.via Wikimedia Commons.

The upper class saw this connection and in fact blamed the outbreak on the poor and recent immigrants. The city’s Board of Health organized a special medical council during the epidemic which claimed, “the disease in the city is confined to the imprudent, the intemperate.”44 One member of high society wondered what the state would be if the disease struck “regular householders.” When someone of the upper class died of cholera, others assumed they must have had some hidden vice which weakened them physically.45

The theory that disease was caused by germs had been proposed, but at the time it was untested. Among the medical community, the dominant understanding was that disease spread through bad odors – smells, what was called miasmas.46

Parallel to the medical understanding was a moral or religious understanding of disease. Many believed that disease – particularly cholera – accompanied immorality. They believed it hit those who were already weakened by some vice such as drunkenness or uncleanliness.47

It wasn’t immorality that caused cholera. In reality, urbanization itself fueled the spread of diseases like cholera. Increased travel and high population density allowed diseases to spread more easily. As America industrialized and urbanized during the first half of the nineteenth century, the average life expectancy for white men actually declined.48

And when it came to cholera, the real issue was access to clean water.

WATER [22:45-26:26]

Although Manhattan was, and still is, an island, there wasn’t a good natural water source. Water from the Hudson and East rivers mixed with the salt water of New York Bay, making it undrinkable.

The wealthier citizens imported their water from other parts of the region, which enabled them to avoid many waterborne diseases. But the poor did not have the same access. Some even had to drink well water drawn from underneath the Five Points neighborhood. The neighborhood was both the worst slum in the city and was built upon a swamp … its water was not clean.49

The urban environment also needed water access to combat one of its greatest threats – fire.

In December of 1835, just a few years after the initial cholera epidemic, a fire swept through New York City.

Fire departments in cities like London used horses and even steam engines to pull their water but recall that New York City used volunteer fire departments that acted like competing frat houses and pulled their own carts to demonstrate their strength. But that takes a lot longer, and in this case, when they reached the fire, they found that the water had frozen in their hoses. To stop the fire, the department used gunpowder to blow up several buildings in the fire’s path to create a barrier. In the end, the fire destroyed 674 buildings, including the remains of the Dutch colony, the oldest part of the city.50

The combination of disease and the Great Fire increased the calls for new access to water. Besides death and destruction, both cholera and fires hurt the city commercially. They closed businesses, kept workers at home, and bankrupted insurance companies. Life insurance companies were among those calling for greater public services like water and sanitation.51

So, in 1835, the city government proposed building an aqueduct to bring fresh water from the Croton River, about twenty miles north of the Bronx. Put before the public, the city voted overwhelmingly in favor of creating the aqueduct. Completed in 1842, it was by far the largest public works project in New York City at the time. The city held public celebrations with songs, cannon fire, and general hoopla.52

Six thousand homes were installed with pipes that gave them direct access to the water. In addition to drinking the water, residents could clean their homes and streets more often. The city even installed fountains in Union Square and City Hall Park showing off their new abundance of water.53

But the aqueduct caused a huge problem for an African American neighborhood called York Hill. City officials chose the neighborhood to construct a holding basin for the water brought in by the aqueduct, essentially destroying the neighborhood and displacing the community.54

And the aqueduct did not totally resolve the city’s health problems. They had access to clean water, but landlords were not required to use water from the aqueduct. Poorer neighborhoods, already hotbeds for disease, still did not often have access to clean water.55

The aqueduct helped, but it didn’t solve everything.

PIGS [26:26-30:30]

Due to the continued unsanitary conditions, there was a second cholera outbreak in 1849. Again, the wealthy blamed the disease on the lower class, and they specifically focused their attacks not just on the poor, but on the pigs they owned.

Why were pigs such a big deal? Because of offal boiling and pig fattening farms.

If, like me, you have never worked in a slaughterhouse, you may be unfamiliar with offal. It is the bones and leftover intestines and organs of an animal—the stuff not typically eaten.

To keep the city fed, butchers slaughtered a lot of animals. By 1850, butchers killed 2500 cattle, 5000 sheep, 1200 calves, and 1200 pigs each week.56 Those animals produced a lot of offal.

The city instructed butchers to dispose of offal in the rivers, which they hoped would wash the material out to sea. But it didn’t. It just floated around and then washed back up on shore.57 So not only were the rivers full of human waste, but pig intestines too. Yummy.

Another solution was to boil the offal. Boiled bones and pig intestines could be used to make soap and candles, and farmers sometimes used the ashes as fertilizer. Offal-boilers even sold the product as food for pigs – which feels wrong. But it was a lucrative business and solved the problem of pig guts in the river.58

Pig fattening farms, also called piggeries, are less exciting. It’s where they fed pigs to get them fat before slaughtering them.

The upper class viewed offal-boiling and piggeries as nuisances. The smell was foul, and they brought public health concerns since they believed disease spread through odors.

On the outskirts of town was a collection of piggeries, offal-boiling plants, and a shanty town occupied by poor residents. The upper class called the area “Hogtown” or sometimes “Stinktown.”59 It was located in present day Midtown, kinda near Carnegie Hall today.

Following the cholera outbreak of 1849, the city spent a decade debating piggeries, offal-boiling, and what to do with Hogtown. As the city expanded farther north, the wealthy argued that Hogtown would hurt commerce and real estate.60

Finally, the issue erupted into what we call the Piggery War. In 1859, New York police began to forcibly remove piggeries and offal-boiling plants from Manhattan. Over the course of three months, they moved through the neighborhoods and destroyed pig pens, boilers, and removed about 90,000 pigs. The lower classes resisted—they were dependent on pigs for their livelihood. Some women even tried hiding pigs in their beds. But the city’s newspapers printed illustrations of the incident and used it to portray immigrants and the poor as dirty, uncivilized, and their women unladylike.63

It was yet another way that the upper class could look down upon the lower class.

COWS AND SWILL MILK [30:30-34:53]

Now I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking “that’s great about the pigs and all, but what about cows?” I’m glad you asked.

Before the city became so dense with people, cows would graze in the open, and their owners sold their milk locally. As the city grew, some New Yorkers purchased milk brought by railroad from outside of the city. However, most people still drank milk from urban cows, but this came at a cost.64

New Yorkers began to rent stalls to board their cattle, rather than letting their cows roam the streets. Many of those stalls were attached to distilleries and breweries.65

This era had some of the highest alcohol consumption of any period in American history. In 1825, the average person over 15 years old drank seven gallons of alcohol a year. For comparison, today the average is closer to two gallons. Alcohol fueled violence, but it was overall still healthier than manure-infested swamp water.66

When brewing alcohol, distilleries produced a by-product commonly called swill – this was processed corn, barley, and rye malt. Distillery owners rented out stalls for cows and fed them swill. This got rid of waste and was a secondary source of income. It all seemed promising. Every day, cows who ate swill could produce up to 25 quarts of milk more than cows fed a normal diet of hay.67 In 1854, an estimated 13,000 cows ate swill.68

But swill milk, as it was called, was an unhealthy product. It was watery and tinted blue, and the fat content was too low to be made into butter or cheese. To make it more visually appealing, venders had to mix in other things like flour, eggs, and chalk. And the meat from these cows also had a bluish hue and spoiled quickly. Swill-fed cows developed sores all over their bodies, and their teeth often fell out.69

A 19th century illustration of "swill milk" being produced by a sickly cow held up by ropes. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Weekly, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Doctors regularly warned of the dangers swill milk posed to children. But poor mothers who worked outside the home had to wean their children off breastmilk, and swill milk was all they could afford. They had no choice but to overlook the unnatural color and health risks. Vendors made the problem worse by advertising swill milk as “pure country milk” – a falsehood that helped them also sell it to the upper classes at a higher price. One estimate in 1853 suggested that swill milk was responsible for 8000 to 9000 infant deaths each year.70

In 1853, the city sent inspectors to investigate the distilleries. But the inspectors left before completing the task because they found the smell to be so rancid.71

After a newspaper exposé highlighted the ongoing issue in 1858, the city council created a commission to again inspect the distilleries. However, they gave businesses a week’s notice, so owners had time to remove sick cows and clean their stables before inspectors arrived. One newspaper reported that the man sent to investigate a distillery never conducted the inspection at all. He just drank a few glasses of whiskey with the owners and went on his way. The common council concluded that it was impossible to prove that a single child died from drinking swill milk. The committee made no substantial changes, and the swill milk industry continued on with no real regulation.72 And children continued to die. The situation was lamentable, but not enough to do anything about it.

So, like water, unclean food remained a real problem for New Yorkers.

PARKS [34:53-41:02]

Early in the century, city officials believed that the Hudson and East rivers would provide the clean air necessary to keep the city healthy. The rivers could clear the bad odors which they believed spread disease.73

The city clearly did not escape disease. The rivers, as we’ve seen, were polluted with human waste and animal entrails. By the 1830s, New Yorkers looked to city parks to provide health and fresh air.74

But health was only one factor in the movement for city parks. After several wealthy residents moved to Brooklyn, which was then a suburb, city developers hoped parks would create desirable neighborhoods and convince the social elite to stay in the city.75 Remember that they were fond of promenading in their fine clothes which, after all, would be easier to do in a landscaped park than along the city’s grimy streets.

Largely funded by taxes paid by property owners surrounding them, parks inevitably ended up in the wealthier neighborhoods.[76] This again fostered a sense of superiority among the upper class.77 The social elite tried to keep their local parks free from African Americans, immigrants, and the poor.78

By the 1840s, however, the city could no longer ignore the social disparity between the rich and poor. Crime rates were rising, disease was spreading, and the city’s hospitals and orphanages were running out of room. In this context, politicians and activists altered their rhetoric about parks. Rather than being places for the elite, they argued the city should create public spaces that everyone could enjoy, regardless of class.79

Beyond public health benefits, developers believed that parks could actually civilize and elevate the lower classes out of poverty. These arguments ultimately culminated in a call for “a great central park.”80

In 1852, a Special Committee on Parks recommended a site stretching from 59th to 106th street and from 5th to 8th avenue. Central Park is located in north-central Manhattan. That’s probably why it’s called Central Park, but sadly we may never know for sure. The council argued that the area was an ideal location for a park, because the rocky and uneven ground would make it difficult for buildings to occupy.81

The land was not widely developed, and the street grid was only a projection that far north. The land was not, however, empty. Irish, German, and African American communities occupied parts of it. This included the mostly African American community of Seneca Village, which we mentioned before. And the village had actually absorbed the displaced residents of York Hill, the African American community displaced by the aqueduct.

When park planners chose the site, Seneca Village had more than 260 residents – approximately two-thirds of which were of African descent and one-third of European descent.82

The park’s engineer-in-chief claimed the occupants were “dwelling in rude huts of their own construction and living off the refuse of the city.”83 Park planners and newspapers portrayed the immigrant communities as rude and dirty, and living with animals. One commentator called them “city barbarians.” Highlighting their class inferiority made it easier for the social elite to justify their removal.84

The city officially approved the site in 1853, claiming the property by right of eminent domain but agreeing to compensate landowners. Those who lived in Seneca Village mostly owned their own land. But many Irish and German immigrants leased or squatted on the land and thus could be evicted without any compensation.85 Residents were allowed to stay until 1857, when the city evicted those who still remained. Workers tore down the 300 plus buildings left behind by former residents.86

Despite evicting families from their homes, officials still claimed the park would benefit all classes. It would be a retreat from the urban environment for all the city’s inhabitants. But wealthy citizens were still worried about a truly democratic park in which the lower and upper classes both had access. One commentator wrote that such parks worked in Europe because, there, there was a defined aristocracy, and everyone knew their place. In America, however, the poor and vulgar would feel entitled to the space. The same commentator worried that the land around the park was being purchased by Irish and German beer-makers and worried that the park would be “nothing but a huge beer garden.”87

To alleviate the fears of the wealthy, park officials created their own police force in 1856. It was authorized by the city police but under park control. They also created strict rules for how to use the space. Visitors could not bring their animals to graze in the park. They could not hunt or carry firearms. They were also not allowed to bathe in the water or collect firewood. It was a clear and intentional departure from the how the land had previously been used, especially by the poor. It was a way for the social elite to instill their values on the lower class.88

CONCLUSION [41:02-42:42]

New Yorkers did not invent class differences. But the rapid urbanization of Manhattan did add a new dimension to the differences. It created a distinct culture among the working class – a culture that was looked down upon by and was frightening to the city’s upper class.

Likewise, public health issues were not new, but urbanization created new challenges as cities struggled to house, feed, and supply clean water to the public.

As New York grew, the classes separated themselves and the countryside got pushed out of the island, transforming the land itself.

The two stories intersect, and together they tell a tale that is messy and wrought with conflict. And New York was only the beginning – by the end of the century, cities across the Nation faced the challenges of class division in an urban environment.

Thanks for listening.

[American History Remix is written and produced by Will Schneider and Lyndsay Smith. For the latest updates, be sure to follow us on Instagram and Twitter. Check out our website for episode transcripts, recommended reading, and resources for teachers. That’s AmericanHistoryRemix.com.]

REFERENCES

Anbinder, Tyler. City of Dreams: The 400-Year Epic History of Immigrant New York. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Baics, Gergely. Feeding Gotham: The Political Economy and Geography of Food in New York, 1790-1860. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York to 1898. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. “American Notes and Pictures from Italy.” In The Works of Charles Dickens: American Notes and Pictures from Italy. Edited by Andrew Lang. Vol. 28 of The Works of Charles Dickens: With Introductions, General Essay, and Notes. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1898. Google Books.

Garner, Anne. “Cholera Comes to New York City.” The New York Academy of Medicine Library Blog, February 3, 2015. https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/2015/02/03/cholera-comes-to-new-york-city/.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Kaplan, Michael. “New York City Tavern Violence and the Creation of a Working-Class Male Identity.” Journal of the Early Republic 15, no. 4 (Winter, 1995): 591-617.

Kasson, John F. Rudeness and Civility: Manners in Nineteenth-Century Urban America. New York: Hill and Wang, 1990.

Lyman, Susan Elizabeth. The Story of New York: An Informal History of the City from Settlement to the Present Day. New York: Crown Publishers, 1975.

McNeur, Catherine. “Parks, People, and Property Values: The Changing Role of Green Spaces in Antebellum Manhattan.” Journal of Planning History 16, no. 2 (May 2017): 98-111.

McNeur, Catherine. Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014.

Rosenberg, Charles E. “The Cholera Epidemic of 1832 in New York City.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 33, no 1 (Jan-Feb, 1959): 37-49.

“Seneca Village Landscape.” Central Park Conservatory. Accessed June 5, 2022. https://www.centralparknyc.org/locations/seneca-village-site.

Stott, Richard Briggs. Workers in the Metropolis: Class, Ethnicity, and Youth in Antebellum New York City. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990.

Wall, Diana diZerega, Nan. A Rothschild, and Cynthia Copeland. “Seneca Village and Little Africa: Two African American Communities in Antebellum New York City.” Historical Archaeology 42, no. 1 (2008): 97-107.

Wilson, Bee. Swindled: From Poison Sweets to Counterfeit Coffee – The Dark History of the Food Cheats. London: John Murray, 2008.

NOTES

[1] Charles Dickens, “American Notes” in The Works of Charles Dickens in Thirty-Two Volumes, ed. Andrew Lang (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1898), 28:94-114. Google Books.

[2] Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 526.

[3] Catherine McNeur, Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 2.

[4] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 117-120; Susan Elizabeth Lyman, The Story of New York: An Informal History of the City from Settlement to the Present Day (New York: Crown Publishers, 1975), 118-120.

[5] Richard Briggs Stott, Workers in the Metropolis: Class, Ethnicity, and Youth in Antebellum New York City (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990), 20.

[6] Stott, Workers in the Metropolis, 63-64.

[7] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 526.

[8] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 182. Tyler Anbinder, City of Dreams: The 400-Year Epic History of Immigrant New York (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), 172-87; Edwin G. Burrows and Mile Wallace, Gotham: The History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 746-47.

[9] Anbinder, City of Dreams, 172-87.

[10] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 176; Burrows and Wallace, Gotham, 744-46.

[11] Stott, Workers in the Metropolis, 168.

[12] Stott, Workers in the Metropolis, 169, 172; Burrows and Wallace, Gotham, 747.

[13] Stott, Workers in the Metropolis, 169-172.

[14] Stott, Workers in the Metropolis, 215.

[15] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 183-188; Burrows and Wallace, Gotham, 747.

[16] Diana diZerega Wall, Nan. A Rothschild, and Cynthia Copeland, “Seneca Village and Little Africa: Two African American Communities in Antebellum New York City,” in Historical Archaeology 42, no. 1 (2008): 99, 103-4.

[17] “Seneca Village Landscape,” Central Park Conservatory, accessed June 5, 2022, https://www.centralparknyc.org/locations/seneca-village-site.

[18] Stott, Workers in the Metropolis, 172.

[19] Stott, Workers in the Metropolis, 191-93.

[20] Stott, Workers in the Metropolis, 192-93.

[21] Catherine McNeur, “Parks, People, and Property Values: The Changing Role of Green Spaces in Antebellum Manhattan,” Journal of Planning History 16, no. 2 (May 2017): 99-100; Lyman, The Story of New York, 123-24.

[22] Stott, Workers in the Metropolis, 216.

[23] Michael Kaplan, “New York City Tavern Violence and the Creation of a Working-Class Male Identity,” Journal of the Early Republic 15, no. 4 (Winter, 1995): 592, 596; Stott, Workers in the Metropolis, 218-19.

[24] Stott, Workers in the Metropolis, 229-31.

[25] Stott, Workers in the Metropolis, 223-23.

[26] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 638; John F. Kasson, Rudeness and Civility: Manners in Nineteenth-Century Urban America (New York: Hill and Wang, 1990), 225-28.

[27] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 528-29.

[28] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 638; Kasson, Rudeness and Civility, 225-28.

[29] Kaplan, “New York City Tavern Violence,” 593, 595.

[30] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 528.

[31] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 99-100.

[32] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 131.

[33] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 101-9.

[34] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 103-5. “Situation of our streets,” New York Evening Post, May 9, 1821, 2, NY Historical Newspapers.

[35] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 104-6.

[36] “CPI Inflation Calculator,” Official Data, accessed January 11, 2021, https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1830?amount=19000.

[37] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 102-5.

[38] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 119-26; Burrows and Wallace, Gotham, 588.

[39] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 109.

[40] McNeur, “Parks, People, and Property Values,” 99.

[41] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 109, 111-13; Burrows and Wallace, Gotham, 589-90.

[42] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 99-100, 112-14; Charles E. Rosenberg, “The Cholera Epidemic of 1832 in New York City,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 33, no 1 (Jan-Feb, 1959): 37.

[43] Anne Garner, “Cholera Comes to New York City,” The New York Academy of Medicine Library Blog, February 3, 2015, https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/2015/02/03/cholera-comes-to-new-york-city/.

[44] Rosenberg, “The Cholera Epidemic of 1832,” 40.

[45] Rosenberg, “The Cholera Epidemic of 1832,” 41-42.

[46] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 470-71.

[47] Rosenberg, “The Cholera Epidemic of 1832,” 42.

[48] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 473.

[49] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 109, 116.

[50] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 529-30; Burrows and Wallace, Gotham, 596-98.

[51] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 531.

[52] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 116-119; Gergely Baics, Feeding Gotham: The Political Economy and Geography of Food in New York, 1790-1860 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2016), 46-48.

[53] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 118; Lyman, The Story of New York, 133-34.

[54] Wall, Rothschild, and Copeland, “Seneca Village and Little Africa,” 98.

[55] Baics, Feeding Gotham, 210, 214.

[56] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 136.

[57] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 136, 139.

[58] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 136-38.

[59] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 160-61.

[60] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 160, 167-69.

[61] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 167-68. See also: Wilbur Miller, “Police Authority in London and New York City 1830-1870,” Journal of Social History 8, no. 2 (Winter 1975): 81-101.

[62] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 163.

[63] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 163-71.

[64] Bee Wilson, Swindled: From Poison Sweets to Counterfeit Coffee – The Dark History of the Food Cheats (London: John Murray, 2008), 154-55.

[65] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 150-51.

[66] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 167.

[67] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 134, 150-51, 153.

[68] Wilson, Swindled, 154-55.

[69] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 151-53. Wilson, Swindled, 155-59.

[70] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 153-54.

[71] Wilson, Swindled, 158.

[72] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 157-59. Wilson, Swindled, 159, 161.

[73] McNeur, “Parks, People, and Property Values,” 98-99.

[74] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 46-47. McNeur, “Parks, People, and Property Values,” 106.

[75] McNeur, “Parks, People, and Property Values,” 102-3.

[76] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 92-93. McNeur, “Parks, People, and Property Values,” 100, 102-3.

[77] McNeur, “Parks, People, and Property Values,” 99-100; McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 92.

[78] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 93.

[79] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 214. McNeur, “Parks, People, and Property Values,” 104.

[80] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 199-201.

[81] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 202.

[82] Wall, Rothschild, and Copeland, “Seneca Village and Little Africa,” 98. McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 203, 209.

[83] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 205.

[84] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 207-8.

[85] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 205. Wall, Rothschild, and Copeland, “Seneca Village and Little Africa,” 98.

[86] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 209-11.

[87] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 215-16. James Gordon Bennett, “The Central Park and Other City Improvements,” New York Herald, September 6, 1857. NY Historical Newspapers?

[88] McNeur, Taming Manhattan, 217. McNeur, “Parks, People, and Property Values,” 106.