VOL. 2 EPISODE 3: TWIN REVOLUTIONS: PART 2

Part two! We continue the story of the twin revolutions–specifically their impact on slavery, political parties, pop culture, and Native Americans in the antebellum era.

INTRODUCTION [00:00-05:03]

In Richmond Virginia, on the morning of March 29th, 1849, employees of the Adams Express company loaded a wooden box onto a train. The company was well known for quick and reliable delivery of mail and packages. The box they took that day was two and half feet high, three feet wide, and two feet deep. On the outside, it was labeled “dry goods.” Just a boring old box.

Except inside that box was a man named Henry Brown. Brown was an African American born into slavery in Louisa County, Virginia in 1815.1

He married a woman named Nancy.2 They had three children together. When his wife’s enslaver sold her and his children to another man, Brown pleaded with him to keep the family together. But he refused. Brown remained in Richmond while his family relocated to the Deep South. With nothing left to lose, Brown decided that he must escape slavery. “I was determined,” he said “that come what may, I should have my freedom or die in the attempt.”

So, in 1849, Henry, with the help of two friends, shut himself inside a wooden box and shipped himself north.

His friend drove the cart carrying him to the train depot. The box was placed in the luggage car of a train which traveled from Richmond to Potomac Creek, Virginia. There, this supposed box of dry goods was transferred to a steamboat enroute to Washington, D.C. In the capital, Henry, along with the other luggage, was transferred to another train and brought to Philadelphia where he was delivered to the city’s Anti-Slavery Society. Henry’s friends had contacted the society prior, and they were expecting his delivery.

The journey had left him weak. When they pried open the box, Brown could hardly stand. But he later reflected that emerging from the box felt like “resurrection from the grave of slavery. I rose a free man.”

Henry Box Brown escapes from slavery by being mailed in a box. Sketch from 1872. Internet Archive Book Images, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons.

In all, Brown’s journey took 27 hours and covered more than 300 miles. The box traveled by several horse-drawn carts, two trains, and a steamboat. But Brown got his freedom.3 Fifteen years prior, this would have been impossible. The railroad connecting Richmond to the cities of the North wasn’t opened until 1836.4 The Adams Express company, with its two-day shipping, wasn’t founded until 1840.5

In part one of this episode, we discussed the twin revolutions in transportation and communication. We saw how in the opening decades of the nineteenth century Americans built a network of roads, railroads, and canals across the once disconnected nation. And a new and improved steam-powered printing press was capable of mass producing the printed word. Newspapers, pamphlets, books, and magazines, all circulated the Nation with ease.

Rapid transportation and communication enabled the growth of a market economy; the market economy transformed family life and gender roles; and at the same time, the Second Great Awakening swept over the country as preachers utilized the new transportation networks and methods of communication to spread evangelical Christianity. If all of this is confusing to you, we suggest you go listen to part one and then come back.

Here, we are going to build upon the story. The twin revolutions also encouraged the expansion of slavery and the so-called cotton kingdom in the South, fostered the growth of public education and popular culture, enabled the rise of modern political parties, and contributed to the forced migration of Native Americans west of the Mississippi.

It is a complex, multifaceted story.

Let’s dig in.

--Intro Music--

[Welcome to American History Remix, the podcast about the overlooked and underexplored parts of American history. We’re glad you’re here!]

SLAVERY [05:03-10:02]

As we saw in part one, among the first areas of American life to feel the impact of the twin revolutions was the economy. The textile industry of the Northeast was the first industry to mass produce goods that could be distributed along the growing transportation network. They were on the forefront of the transition to a market economy, a capitalist rather than agrarian economy.

Now, textile mills made cloth out of cotton, cotton was grown and harvested in the southern United States by enslaved African Americans.

In the Atlantic regions of Virginia and North and South Carolina, enslaved persons traditionally grew rice and tobacco. The rich soil of the Deep South, however, was an ideal location for cotton planting, but cotton was labor intensive and not always worth the investment. Then, in 1792, Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, a device that made cotton harvesting easier and more cost-effective. So, slave owners flooded the Deep South, establishing cotton plantations, and giving the region the population that it needed to foster new states. Mississippi joined the Union in 1817, Alabama in 1819, just as those textile mills in the Northeast were taking off.6

African Americans slaves using the First cotton-gin, 1790-1800, drawn by William L. Sheppard. William L. Sheppard, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Founding Fathers, many of whom were slave owners, knew that slavery was not compatible with the values of liberty and equality, but they made little to no effort to actually end slavery. They had assumed that it would eventually grow weaker and die a natural death. They were wrong. Slavery grew stronger in the Early Republic.7

Great Britain and the United States outlawed the international slave trade in 1807. But the internal slave trade was strong. Incredibly strong, in fact. Outside of plantation slavery itself, the slave trade was the biggest industry in the South.8 Historians call enslaved Africans’ journey from Africa to the Americas the “Middle Passage.” In the United States, slave traders created their own transportation network to bring slaves from the seaboard to Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. The journey from the seaboard to the Deep South, historians call the “Second Middle Passage.”9

A system of roads and scattered storehouses and pens made transportation easier – for the traders at least. They often put children on wagons. But the men and women they enslaved were bound together in chains and marched on foot.

Before forced relocation, dealers carefully inspected enslaved persons and then used the updated printing technology to advertise to potential buyers. Planters, for example, desired young men to work the fields and young women to produce more slaves. In their advertisements, sellers would note if a girl was “a good breeder.”10

In the 1810s, slave traders forced about 120,000 men and women to the Deep South. And the numbers only grew. During the 1830s, slave traders tore 300,000 men, women, and children from their families. As we saw in the story of Henry Brown, slave owners made little to no effort to keep families together. Even those who did remain together lived in constant fear of losing their loved ones, because any day they could be sold.11

An enslaved man named Francis Fredric experienced the migration himself when his owner decided to move west. Fredric recalled seeing enslaved men and women “down on their knees begging to be purchased to go with their wives or husbands” and “children crying and imploring not to have their parents sent away.”12

Their cries made no difference.

All of this to grow and sell some g**d@$/ cotton. Cotton was worth a lot of money. It fueled the textile mills in the Northeast and slave plantations in the South.13 Nothing happened in isolation, it was all connected.

EDUCATION [10:02-13:58]

Of course, no one was hurt more by slavery than enslaved persons. We’re not arguing otherwise. But the southern slave economy, in the long run, also hurt free whites, because it held back public education in the region, especially for poor whites who could not afford private education like wealthy plantations owners could.

We mentioned in part one, the market economy created a lot of new jobs—these were jobs that required a basic level of education. The growing business world required lawyers, new factories needed factory managers who could read, write, and do math. And expanded print culture required journalists and publishers.

The increased need for education coincided with another trend—expanding voting rights, as most states dropped their property requirements to vote. In this environment, advocates began calling for public education. Public schooling was necessary, they argued, for a healthy republic. It could bond individuals together, create social cohesion, and provide them with the skills they needed to participate in politics.14 So, multiple forces, economic, social, and political created a boom in the education system.

But all of these forces were strongest in the North. The Southern economy was based on slavery, not manufacturing. And southern states were among the last to drop their property requirements to vote. Therefore, schooling expanded more in the North than it did in the South. Young men in the North received the skills they needed to enter the market economy. Their southern counterparts did not benefit from public support for education, and their career options were more limited.15

In Massachusetts we can see the shift most clearly – they were a hub for the textile industry and were on the forefront of public education. In 1837, they became the first state to establish a Board of Education.16 The Secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education was Horace Mann. Mann helped establish what he called “common” elementary schools. These schools were tax-supported, tuition-free, and open to anyone. Mann also published one of the first professional journals on education, called The Common School Journal, which he used to bring important issues in education before the public. And, in 1852, Massachusetts passed a law requiring elementary school attendance for young children.17 School became mandatory.

Other teachers mimicked the itinerate preachers of the Second Great Awakening, which we talked about in part one. They traveled the Nation and established their own temporary schools. They’d teach a community writing skills or give lectures on science. They’d stay for a few weeks and then journey on to the next town.18

The education system reinforced the market economy. Local schools hired thousands of teachers for yearly contracts. Teachers were often in their late teens or early twenties. They would teach for a few years, save up money, and then enter into the business world. Then the expansion of commerce increased the need for educated workers, and the system reinforced itself.19

But this kind of public education didn’t move south until after the Civil War.

POPULAR CULTURE [13:58-19:52]

The revolution in communication also fostered the growth of American popular culture including literature, theater, and music.

The decreased cost of publishing, easier distribution, and improved literacy rates made books increasingly popular and accessible to a mass audience. This was, in many ways, a golden age of American literature.20

First came the transcendentalists in the 1820s – a group of writers from Concord, Massachusetts.21 Members included Ralph Waldo Emerson, who made a living writing and traveling the Nation (on the new transportation network) and speaking to audiences. There was Henry David Thoreau who wrote Walden Pond after living alone in a cabin for nearly two years.22 Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote The Scarlett Letter and The House of Seven Gables.23 Margaret Fuller edited a transcendentalist magazine and argued for women’s rights.24

That’s only the transcendentalists – they were just one group of writers. At lot of other important works of American literature come from the same era. Herman Melville released Moby Dick in 1850. In 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Walt Whitman self-published Leaves of Grass, his famous collection of poetry, in 1855. Meanwhile, Edger Allen Poe wrote poems like The Raven and Annabelle Lee, and short stories like The Tell-Tale Heart. He pioneered detective fiction and horror. He also wrote literary criticism, analyzing the works of other authors.25

The printing technology also allowed African American voices to engage with the Nation.

The 1849 copy of the poem "Annabel Lee" by Edgar Allan Poe. 1849 fair copy, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Frederick Bailey was born into slavery in Maryland in 1818. As a young man, he taught himself to read. In 1838, he disguised himself, escaped to the North, and changed his name to Frederick Douglass. Douglass published his autobiography in 1845. He began an abolitionist newspaper called the North Star in 1847. He is perhaps the greatest communicator, the finest wielder of words in American history. And for four years he published his newspaper weekly, arguing against slavery.26

Not all the literature was serious, however. The new technology allowed a variety of genres to prosper, such as Dime novels (named for their cheap price) and adventure stories.27 Had these authors not been able to distribute and earn a living from their work, who knows what American literature would look like.

Theater became increasingly popular during the antebellum period too. It had been generally frowned upon during the revolutionary era – many believed it was emotionally indulgent. Though it retained a stigma among the following generation, going to the theater became a popular pastime for the growing urban working class. Theater troupes used the new transportation network to travel the Nation.28

On top of this, there developed the first national, American music – blackface minstrelsy. Musicians performed in blackface and used exaggerated mannerisms and dialect to mock African Americans. Many of the songs they performed were actually adapted from African American music. In essence, white performers took African American music, repackaged it, added new words, and presented it to a general audience. It’s the same thing that happened with Rock and Roll a century later.

1848 image of Adams, Casey, & Howard; blackface minstrel trio. See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Minstrelsy was a fluid art form. Each performer could adapt a song and perform it as they saw fit. So sometimes songs would be performed in blackface, sometimes not. But many classic American songs come from minstrelsy: “Oh Suzanna,” “Campton Races,” “She’ll Be Coming Round the Mountain,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” and my choice for the worst song ever written: Stephen Foster’s “The Glendy Burk.”29 You can look it up, or take my word that it’s terrible.

Many of the performers who pioneered this genre were from the growing and urban North, and their songs had great appeal to urban, working-class men.30 Like authors and actors of the time, minstrel troupes traversed the country on the new transportation network, performing their songs to new audiences. The new printing technology helped too. Newspapers printed advertisements for upcoming shows, and the growing publishing industry printed and sold sheet music.

So, in total, there was a flurry of books, songs, poems, magazines, and shows as writers and performers created for the first time a truly American popular culture.

Pretty much every song I learned in elementary school music class and all the literature I read in high school came from this period. And, like everything else we’ve been talking about, it wouldn’t have been possible without the revolutions in transportation and communication.

PARTY FORMATION [19:52-34:56]

So far, in these episodes, we have covered how the twin revolutions affected the economy, family, religion, slavery, education and popular culture. But why stop there? Let’s talk about politics.

In our previous episode about the creation of the US government, we discussed the rivalry between the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans and the Federalist Party. By 1812, the Federalist Party was basically defunct, and the Democratic-Republican Party was the only national party left. Today it would be shocking if a political party just disappeared (as much as we might like them to), but in the early 1800s, loyalty to specific politicians or to a region was much stronger than adherence to a party.31

Early parties were loose personal alliances of individuals with a similar philosophy, not organized vehicles for recruiting candidates and winning public support. Even the name of Jefferson’s party was flexible. Sometimes we call them the Jeffersonian Republicans, or the Democratic-Republicans, or the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans.32 The whole system was loose.

Then came the election of 1824. This was a weird election. To start, it was a four-way race. The candidates were John Quincy Adams, the Secretary of State and son of former president John Adams; Henry Clay, the Speaker of the House; William Crawford, the Secretary of the Treasury; and Andrew Jackson, a war hero and senator from Tennessee, who ran as a political outsider.33 Making the election even weirder to modern observers, is that John C. Calhoun was the vice presidential candidate for both John Adams and Andrew Jackson.34 Since there was only one political party, they were all running together and against each other at the same time.

A political cartoon depicting the presidential election of 1824 as a footrace between the four candidates–John Quincy Adams, William Crawford, Andrew Jackson, and Henry Clay. David Claypoole Johnston, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

It gets weirder too. Because in 1824, none of the candidates won the minimum number of electoral votes required to be victorious. And, when there is no clear winner, the 12th Amendment of the Constitution states that the House of Representatives should choose the president. Of the four candidates, Andrew Jackson had the most votes, but he was running as an outsider, and his famously temperamental attitude made him unpopular in Washington. John Quincy Adams had the second most votes. He and Henry Clay, had similar policies, so Clay, who, remember, was the Speaker of the House, gave Adams his support and convinced his supporters to likewise back Adams. Then he and Adams each won over delegates from states where Jackson had won the popular vote. This alliance won the election for John Quincy Adams, and he became the sixth president of the United States.35

Andrew Jackson was pissed. He called it a “corrupt bargain.” On one hand, Jackson made a good point: he received more votes than anyone else. But in a split election, some sort of coalition is mathematically required for there to be a winner. Some sort of alliance was inevitable. So, was it corrupt? What do you think?36

Either way, the one-party system was breaking. The alliance between Adams and Clay laid the foundation for what became the Nationalist-Republicans. The Jackson and Crawford camps formed the Democratic-Republicans. Though again, these names were nebulous and largely tied to political personalities. During Adams’ presidency, the press referred to “Adams’ Men” and “Jackson’s Men.”37 And the two men prepared for a rematch in 1828.

And the whole thing kept getting weirder. John C. Calhoun, while serving as Adams’ vice president, began to move farther away from Adams’ camp and towards Jackson’s. In 1826, Calhoun, while serving as vice president, pledged to support Jackson in the upcoming election.38

So, what actually separated the two camps? Adams’ political plan was based on what he called “internal improvements.” He proposed a plan for the federal expansion of transportation, which included a second national road, this one from Washington, DC to New Orleans, the creation of the Department of the Interior, a national university, a national observatory, and the adoption of the metric system.39 Not all of these came to fruition. In essence, he favored government investment in infrastructure and education to foster a diversified economy.

Jackson, meanwhile, effectively used the rhetoric of states’ rights and opposed a national system. He was not wholly opposed to improvements in transportation, but he believed they should come through the states. Rather than a diversified economy, he favored an expansionist America with new lands in the West opened up for slave labor. He also opposed paper money and a national bank.40

It was Jackson’s camp that began to organize into the first modern political party, with organized campaigns, conventions, and patronage. But to truly understand this process we need to look at one other towering figure, by far the most influential politician in American history. You know who I’m talking about – Martin Van Buren. Ok, I’m exaggerating, but perhaps not as much as you might think.

Martin Van Buren eventually became the 8th president of the United States. But his impact on America doesn’t stem from his presidency. Van Buren was the architect of the political system that formed around Andrew Jackson. He’s the granddaddy of modern political parties. Let’s back up a bit.

New York was at the forefront of many of the developments we’ve been talking about, and politics is no exception. There, Dewitt Clinton was governor on and off from 1817-1828, and he oversaw the construction of the Erie Canal. Remember “Clinton’s big ditch”? That’s this guy.41

Martin Van Buren was Clinton’s political rival, but Clinton’s popularity and the booming economy made it difficult to challenge him. So, Van Buren had to change the conversation. He and his followers began calling for the state to eliminate its property requirements for voting. Clinton and his allies were not actually opposed to removing voting restrictions, but Van Buren used the press to portray Clinton as an aristocrat standing in the way of popular democracy. It was a very effective political maneuver, and it showed that Van Buren knew how to utilize the new methods of communication to shape public opinion.

Van Buren’s followers succeeded in defeating Clinton in the 1822 election. And, once in power, they created a system of patronage that rewarded their followers with government positions. Clinton eventually returned to power in 1825, but he died three years later, and Van Buren remained the biggest figure in New York politics.

Then, Van Buren brought his experience in political organization, in managing public opinion, and in rewarding loyalty to the federal level when he allied himself with Andrew Jackson.42 Van Buren was good at his job. He helped create the strategy for the 1828 campaign. He directed his followers and the press to label Jackson’s opponents as “Federalists,” implying they were aristocrats. Meanwhile, to garner support from the masses, they championed voting rights for the common man. Under his guidance, the Democratic-Republicans held state conventions and rallies and used the press to battle for public opinion.43

Politics was no longer just a rivalry among upper class gentlemen. There was broad political organization. And it was Van Buren who figured out how to capitalize on the communication revolution to form this political machinery.

But, of course, Jackson, not Van Buren, was the central figure of the Democratic-Republican Party. While this coalescing party did have policy positions, it emphasized Jackson as a person. His personality and image as a war hero and representative of the common man made him popular.

But the 1828 election was dirty. Both Adams and Jackson took advantage of the advancements in printing to create their own newspapers. Publications were filled with personal attacks, fake news stories, and America’s first political sex scandal. Jackson’s wife, the papers revealed, was married to another man when she and Jackson began living together.44

Andrew Jackson portrait by Thomas Sully (1824). Thomas Sully, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In the end, Jackson’s popularity won out. He captured 56% of the popular vote and became the seventh president of the United States.45

Once elected, Andrew Jackson embraced Van Buren’s system of patronage. And it’s important to note that this system was new. John Quincy Adams used political appointments to win over his rivals. He would offer positions in his administration to those who thought differently. He wanted to lead a government by consensus, reaching past ideological lines. Jackson used political positions to reward his followers. Rather than working with those of differing opinions, Jackson inspired party loyalty. If everyone fell in line, they’d get their reward. Adams’ model was certainly the more noble. Jackson’s was by far more effective.46

So, what did Jackson’s presidency look like? Well, there’s a lot to it. Jackson remained a controversial figure. He waged a figurative war with the Bank of the United States and at one point during his presidency, South Carolina tried to invalidate federal law. Those are fun subjects, but we’re not actually going to talk about them. Instead, we want to point out that the two-party system continued to develop under his presidency.47 And his party, became known simply as the Democratic Party.

George Washington had warned the Nation about the danger of political parties. Many in the Nation retained some distrust for organized politics. Much of the criticism of Jackson was regarding his party’s organization But, faced with a powerful political machinery, Jackson’s critics had to adopt the same practices in order to survive. The congressional opponents of Jackson began to call themselves Whigs. When Abraham Lincoln served in the House of Representatives in the 1840s, he was a Whig. Regarding the parties, Lincoln said, “They set us the example of organization and we, in self-defense, are driven to it.”48 But the Whigs did not organize immediately. Their first party convention wasn’t until 1839.49

The Whig platform centered on the policies of Henry Clay, Jackson’s rival who had supported John Quincy Adams. Clay called his own policies the “American System.” He envisioned an interconnected national economy. Farmers were a market for manufacturers and manufacturers were a market for food and raw materials grown on farms. He called for government aid to build roads, railroads, and canals. To fill the jobs created by this economy, the Nation needed an educated and literate population, so the Whigs supported the expansion of public education.50

Democrats favored the expansion of slavery and cotton plantations into the western territories. They promoted agriculture. If you’ve been paying attention, you’ll notice we’ve talked about these subjects already – the two parties emphasized different sides of the market economy. But, of course, the sides were connected since Northern industry ran on Southern cotton. But the difference in emphasis caused real political division.

And while they fought with each other, both sides used the advancements in communication and transportation to organize themselves into modern political parties.

Party loyalty has been a dominant force in American politics ever since.

INDIAN REMOVAL [34:56-43:30]

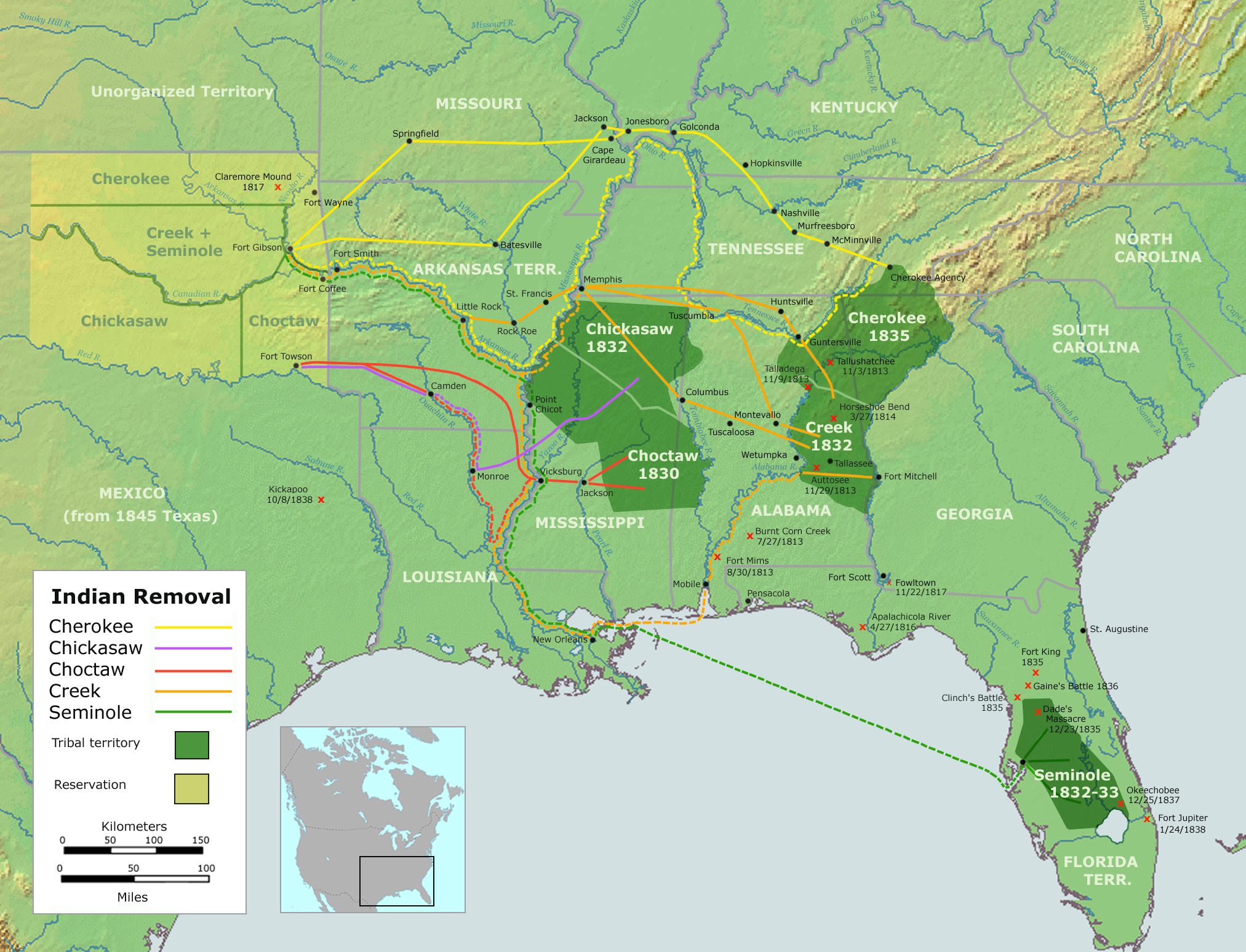

This brings us to our final topic—Indian Removal. It’s one of the darker moments in American history. This was when federal and state governments forced several Native tribes, such as the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Creek off of their lands.

For our purposes, we’ll focus on the Cherokee tribe, originally from Georgia.

Let’s back up a bit. In 1802, Georgia agreed to cede some of the land it possessed under its colonial charter, allowing for new states to form in the Deep South. In exchange for giving up this territory, the federal government agreed to purchase Cherokee land within the state of Georgia. Twenty-five years later, Anglo-Americans in Georgia had grown frustrated that the federal government had not purchased more land for them. But the government couldn’t buy the land because the Cherokee refused to sell it.51 The deal had assumed that the Cherokee would give up their land. It had been a little presumptuous.

An 1884 of the former territorial limits of Cherokee Nation. National Archives and Records Administration, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Those of European descent had long claimed that Native Americans didn’t properly use the land – that Natives were backwards, and uncivilized. In the past, they used such claims to justify taking the land.

But by the early 1800s, many within the Cherokee tribe had embraced Anglo-American farming practices. Among the Cherokee were wealthy planters who used African American slave labor to grow cotton, just like their white counterparts did. Other wealthy members of the tribe opened stores and taverns along the growing network of roads or ran their own toll roads and ferries.52

By the 1820s, they had developed a writing system for their language, and in 1828 the tribe began to publish a newspaper called the Cherokee Phoenix.53

So, Cherokee farms produced cotton for market, and the tribe participated in the transportation and communication revolutions. Old justifications for taking their land didn’t apply anymore. Anglo-Americans in Georgia were frustrated, but that did little to deter them from wanting to take Cherokee land.

Then, Andrew Jackson was elected to the presidency in 1828. Jackson had a long history of violence against Native Americans. During the War of 1812, he led his men to slaughter a Creek village, killing 600 Native Americans, most of them women and children.54

Emboldened by Jackson’s election, the Georgia State Legislature decided to exert its power over Cherokee land, suspending the political sovereignty of the tribe. In 1830, Congress passed the India Removal Act which allocated funds to expel Native Americans from their lands and relocate them to the West.55

The Cherokee defended their sovereignty and appealed to the United States Supreme Court. The Court ruled in favor of the Cherokee Nation in 1832, ruling that it was unconstitutional for Georgia to ignore Cherokee sovereignty. Georgia, however, ignored the Supreme Court. Despite the ruling, they refused to recognize the Cherokee right to self-government and began a lottery system for awarding Cherokee land to the state’s white residents.56 Andrew Jackson, likewise, rejected the Supreme Court’s decision. The Chief Justice of the Court was John Marshall. Jackson’s response to the ruling was, reportedly, to say “John Marshall has made his decision: now let him enforce it!”57

What motivated all this? Why did they want the land this badly?

White settlers coveting Native land was not new. It’s as old as colonization. But, in the early 1800s, hunger for land in Georgia was particularly fierce. As we’ve seen, the American population was rapidly growing. White Americans were moving farther west while Georgia still had land within its borders owned by Native Americans.58 This created intense public pressure on the Cherokee to give up their land.

The cotton boom added another dimension. Cherokee land included several fertile river valleys suitable for growing cotton to feed the hungry textile mills in the North.59

The discovery of gold on Cherokee land in 1830 only added to the fanaticism. Many white settlers rushed to the region and violently pushed Cherokee off their land.60

Georgians even turned their desire for land into a popular song, which went:

“All I want in this creation,

Is a pretty little wife and a big plantation,

Away up yonder in the Cherokee Nation.”61

But there was yet another factor. In addition to farmland, Georgians wanted to use Cherokee land for internal improvements. They wanted to use railroads and canals to connect the Atlantic Ocean with the Tennessee River, and the best way to do that was to go through Cherokee land.62

It was not the first time Americans took Native land, and it was not the last time either. But in this case, the hunger for land and ultimately the removal of the Cherokee was shaped by the market economy, the demand for cotton, and the transportation revolution.

But the hunger did not guarantee white settlers would succeed. Cherokee leadership, led by Principal Chief John Ross, still resisted removal, as did the majority of the Cherokee people. However, a small group believed that ceding their land was now their only option. This group was dubbed the “Treaty Party” and centered around Major Ridge, a veteran of the Creek War and a wealthy planter. The other two leaders were his son-in-law John Ridge and Elias Boudinot. These men were wealthy members of the tribe but were not as prominent as Principal Chief Ross. The Treaty Party members were quickly removed from the tribal council. But the United States government still negotiated with the Treaty Party, even though they did not hold any recognized leadership positions.63

This illegitimate group agreed to a treaty ceding all Cherokee land in Georgia and arranging for their people to move west of the Mississippi. Today, this would be like if I, as an American, went to a foreign nation and agreed to some treaty on behalf of the United States. It might be fun to try, but I have absolutely no authority do so.

Map of the route of the Trails of Tears — depicting the route taken to relocate Native Americans from the Southeastern United States between 1836 and 1839. User:Nikater, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Principal Chief Ross and the actual Cherokee leadership petitioned Congress to reject this illegitimate treaty. But in 1836, Congress ratified it anyway and gave the Cherokee people two years to remove themselves from their land. During the winter of 1838/39, the Cherokee tribe was forced west to Oklahoma, most of them on foot. The journey earned the name the “Trail of Tears.” Of the 12,000 people who were forced to migrate, 4000 died due to the harsh weather and unsanitary conditions in the camps. Once in Oklahoma, the Cherokee blamed Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot for the loss of their land and the deaths that occurred on the way west. So, they murdered the three men.64 Like we said before, this was a dark chapter in American history.

CONCLUSION [43:30-45:34]

It’s not a simple story we’ve been telling in these episodes. The impact of the twin revolutions was far reaching.

There’s the story of the Market Revolution, and then the story of public education, the expansion of slavery, utopian societies, and the rise of political parties, etc. Each one told as if they stood alone – like they’re parallel lines which never intersect. But the past is more complicated than that. The stories bump into each other, interact, and influence one another.

The ability for Americans to travel and communicate quickly changed everything.

In part one of this episode, we claimed that the transportation and communication revolutions sent ripples through American society. Perhaps, it would be more accurate to say that they sent shockwaves that reverberated through the whole of American life. And, for good or ill, nothing was the same after.

Thanks for listening.

[American History Remix is written and produced by Will Schneider and Lyndsay Smith. Special thanks to our friend Chelsea Gibson for reviewing an early draft of this episode. We truly appreciate her many insightful contributions, questions, and corrections. Of course, any inaccuracies remain our responsibility, but we appreciate Chelsea’s generous input! For the latest updates, be sure to follow us on Instagram and Twitter. Check out our website for episode transcripts, recommended reading, and resources for teachers. That’s AmericanHistoryRemix.com.]

REFERENCES

Appleby, Joyce. Inheriting the Revolution: The First Generation of Americans. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2000.

Berlin, Ira. Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003.

Brown, Henry Box. Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself. Manchester, England: Lee and Glynn, 1851. Google Books.

Foner, Eric. Give Me Liberty!: An American History. New York: W.W. Norton, 2011.

Foner, Eric. The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Johnson, James A., Diann Musial, Gene. E. Hall, and Donna M. Gollnick. Foundations of American Education: Perspectives on Education in a Changing World. Boston: Pearson, 2011.

Maisel, Louis Sandy. American Political Parties and Elections: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Perdue, Theda and Michael D. Green. The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford/ST. Martins, 1995.

“Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad Company, 1837–1983.” Virginia Museum of History & Culture. Accessed June 12, 2021. https://virginiahistory.org/research/research-resources/finding-aids/richmond-fredericksburg-and-potomac-railroad-company-1837.

Robbins, Hollis. “Fugitive Mail: The Deliverance of Henry ‘Box’ Brown and Antebellum Postal Politics.” American Studies 50, no. 1/2 (Spring/Summer 2009): 5-25.

Saxton, Alexander. "Blackface Minstrelsy and Jacksonian Ideology." American Quarterly 27, no. 1 (March 1975): 3-28.

Sellers, Charles. The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815-1846. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Taylor, Alan. American Republics: A Continental History of the United States, 1783-1850. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2021.

Wood, Gordon S. Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Young, Mary. “The Exercise of Sovereignty in Cherokee Georgia.” Journal of the Early Republic 10, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 43-63.

NOTES

[1] Henry Box Brown, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself (Manchester: Lee and Glynn, 1851), 1.

[2] Brown, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, 33.

[3] Brown, Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, 51-56.

[4] “Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad Company, 1837–1983.” Virginia Museum of History & Culture. Accessed June 12, 2021. https://virginiahistory.org/research/research-resources/finding-aids/richmond-fredericksburg-and-potomac-railroad-company-1837.

[5] Hollis Robbins, “Fugitive Mail: The Deliverance of Henry ‘Box’ Brown and Antebellum Postal Politics,” American Studies Vol. 50 (Spring/Summer 2009): 7, 12.

[6] Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 125.

[7] Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 518-19.

[8] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 52.

[9] Ira Berlin, Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003), 172.

[10] Berlin, Generations of Captivity, 170-72.

[11] Berlin, Generations of Captivity, 168; Joyce Appleby, Inheriting the Revolution: The First Generation of Americans (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2000), 70-71.

[12] Alan Taylor, American Republics: A Continental History of the United States, 1783-1850 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2021), 159.

[13] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 132.

[14] Charles Sellers, The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815-1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 367.

[15] Appleby, Inheriting the Revolution, 104.

[16] Sellers, The Market Revolution, 366-67.

[17] James A. Johnson, Diann Musial, Gene E. Hall, and Donna M. Gollnick, The Foundations of American Education: Perspectives on Education in a Changing World (Boston: Pearson, 2011), 40; Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty!: An American History (New York: W.W. Norton, 2011), 438-39; Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 452-53.

[18] Appleby, Inheriting the Revolution, 108.

[19] Appleby, Inheriting the Revolution, 104.

[20] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 232, 618, 627-28.

[21] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 618-20; Sellers, The Market Revolution, 375-80.

[22] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 623-24.

[23] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 633.

[24] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 622-23.

[25] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 632-33.

[26] Taylor, American Republics, 187-88; Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 643.

[27] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 632-33.

[28] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 636-38.

[29] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 636-41.

[30] Alexander Saxton, "Blackface Minstrelsy and Jacksonian Ideology," American Quarterly 27, no. 1 (1975): 5-7.

[31] Louis Sandy Maisel, American Political Parties and Elections: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 33-34.

[32] Wood, Empire of Liberty, 313-14.

[33] Maisel, American Political Parties and Elections, 33-34; Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 203-7.

[34] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 249.

[35] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 208-10.

[36] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 247.

[37] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 210, 251.

[38] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 249-50.

[39] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 252-54.

[40] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 279, 358-59.

[41] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 238.

[42] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 237-41.

[43] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 276-79.

[44] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 277-79.

[45] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 280.

[46] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 259.

[47] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 378-80.

[48] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 584.

[49] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 486.

[50] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 270-71; Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010), 34.

[51] Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green, The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents (Boston: Bedford/ST. Martins, 1995), 17.

[52] Perdue and Green, The Cherokee Removal, 13.

[53] Perdue and Green, The Cherokee Removal, 14.

[54] Taylor, American Republics, 130.

[55] Taylor, American Republics, 280-81; Perdue and Green, The Cherokee Removal, 18-19.

[56] Perdue and Green, The Cherokee Removal, 18-19.

[57] Sellers, The Market Revolution, 311.

[58] Perdue and Green, The Cherokee Removal, 15.

[59] Perdue and Green, The Cherokee Removal, 15; Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 342; Quote from Sellers, The Market Revolution, 272.

[60] Taylor, American Republics, 279.

[61] Taylor, American Republics, 279.

[62] Mary Young, “The Exercise of Sovereignty in Cherokee Georgia,” Journal of the Early Republic 10, no. 1, (Spring, 1990): 44-46.

[63] Perdue and Green, The Cherokee Removal, 20.

[64] Perdue and Green, The Cherokee Removal, 20; Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 416.